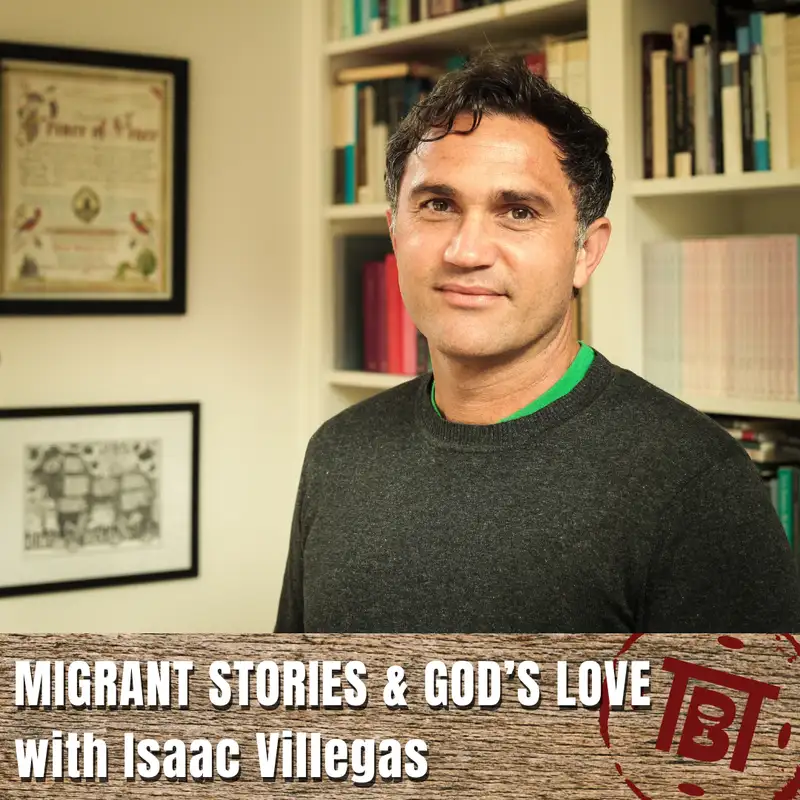

Migrant Stories & God's Love with Isaac Villegas

Episode 42 (Isaac Villegas)

===

Andrew Camp: [00:00:00] Hello, and welcome to another episode of The Biggest Table. I am your host, Andrew Camp. And in this podcast we explore the table, food, eating and hospitality as an arena for experiencing God's love and our love for one another.

And today I'm joined by Isaac Viegas.

Isaac is an ordained minister in the Mennonite Church who is also involved in the work of community organizing and activism for Immigrant Justice. He's a columnist for the Christian century and the author of Migrant God, a Christian Vision for Immigrant Justice. He has served as the president of the NC Council of Churches and is on the executive board of his denomination. He lives with his wife in North Carolina.

So thanks for joining me today, Isaac. It's great to have this conversation.

Isaac Villegas: Well, thanks, Andrew. I'm very, yeah, grateful that you want to talk to me about all these things. Yes. A lot of gratitude for, for your willingness to to talk.

Andrew Camp: No, I appreciate it. You know, and, uh, I think I shared when I was emailing you, when my wife and I lived in Park [00:01:00] City, we had the privilege of working with some Latinos and starting, um, a Spanish speaking congregation and just getting to know the migrant population there.

Um, because Park City's a resort community. You have, you know, they're all involved in the service industry. Um, and so they made up 20% of the community and, um, we just got to know them and their love and hospitality for us. Um, and so yeah, it's getting to know them and getting to know their stories, changes how you view, um, migration issues.

You know, at least for me, that's how, you know, I became aware is just being in relationship with people.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah, no, that's exactly right. I mean that, yeah, no, that, that is exactly, I'm just thinking about my own story with my parents. My parents are both immigrants and they're alive growing. So I grew up in Tucson.

So just on the other side of the state from where you are. Yeah. Um, and yeah, my mom works in the service industry and like that's, that's been her job her whole life. And [00:02:00] yeah, I mean that immigrants make us who we are. I mean, that's just make me who I am and our communities, what they are and pay taxes and fund this country and all that.

Andrew Camp: What I really appreciated about your book as I was reflecting on it, is that you, you challenge us and force us to look at the devastating stories of migrants, but then you also give us a beautiful picture of what is possible as people are involved. Um, 'cause you share some beautiful stories of remembrance and being involved in the work and what it does, um, for our own souls.

And so like, it's a challenging book. It's not an easy book, but it's, it's a book that I think paints a beautiful picture of what is possible as we adopt a more biblical imagination.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah, no, that's what I was hoping to do. My, I like, on the one hand there are important biblical arguments to be made, right?

And there are those books out there [00:03:00] that kind of are like the apologetics. Yeah. Here are the biblical and theological reasons why we as Christians, um, care for the foreigners in our midst. And you know, you do your Leviticus stuff, you do whatever it might be. And yeah, all of that is super important. I'm grateful that those are out there.

Um, and then on the other hand, there are those books that are just like, Hey, let me give you an analysis of our what has made this country anti-immigrant and it's like history, story, like those kinds of storytelling and um, also very important and super depressing.

And I guess what I wanted to do or is like share these stories of like good news that I've been a part of that I've seen and like they give me hope, these stories, what communities, what people are up to. And I'm like, I need, and I, you know, like I replay these stories in my mind sometimes over the years. Like, this was awesome. I can't believe this is going on now. God's working in this way. Um, and since I replay them in my [00:04:00] head, I thought maybe I could share them with others just to share a little hope maybe.

Um, so yeah, so I'm grateful that you both recognize that like it's tough stuff and people are doing, important godly things in the world, and I'm grateful that they're doing that.

Andrew Camp: No, for sure. Um, and as we begin, you also. Language isn't important as we talk about this issue. And so can you help our listeners who may not be familiar with the language, like what, what language, why is language important and what language should we be using as Jesus followers to talk about this issue?

Isaac Villegas: Mm-hmm. Yeah. That's interesting. I haven't thought about that, but you are so right. Our language isn't, so basically like at the end of the day, how language works for us is, um, I think about ethics. Our ethics, uh, ethics is all about how we act in the world. Yeah. And how we act in the world is very much, [00:05:00] uh, shaped by what we can see, um, what we can experience, what we can smell, taste, you know, that whole register of of, of who we are.

Um, and if we want to share those experiences of the world with each other, I. We have to use language. So, um, this is saying that I got from my, uh, professor Stanley Hauerwas is you can only act in the world. You can see, and you can only see in the world, you can say. Mm-hmm. And what that means is like our whole language, our concept shape, they mediate how we experience the world together.

Um, 'cause you know, we think with a language, right? Um, and so how we describe the situation is of what's going on is super important for how we understand what's going on so that we can talk to each other about what's going on so we can figure out what we can do together is basically working backwards from that way of thinking about it.

And yeah, I mean, in my, [00:06:00] I mean, two things to say on that, along those lines in the book is like one, just on a very personal level, like I try to include Spanish in the book, um, because, you know, I. I grew up thinking in Spanish. Mm-hmm. And it's still there and sometimes I have a hard time thinking about like what a word might be in English.

Hmm. Um, and that shapes how I experienced the world. Um, so yeah, I include Spanish as a way, but hopefully it wasn't too offputting. Was it off putting to all the, the Spanish that was in there?

Andrew Camp: Not to me. Like my wife's fluent in Spanish. Okay. You know, I worked in the restaurant, so I have restaurant Spanish and so like I could piece it together.

Right. Um, but it did again, it, like, it hones you in, it makes it immerses you more fully in into the issues.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah. So, yeah. Right. No, that's great. Yeah. So in general, I try to include translation, but every once in a while I don't, because it was such an experience, I like to translate it into English or a [00:07:00] phrase or whatever it might be.

Just didn't quite work. So I just let it be, but I, yeah, I don't, hopefully it's not off, but, so on one side there's that, there's Spanish. Yeah. Um. Oh, go ahead. No, go ahead. Yep. Okay. And then on, on the other is like how we describe what's going on in our world in relationship to immigrants. So I don't talk about the immigrant crisis, let's say, like that never shows up, is, you know, this sense of, oh, we are in this, uh, crisis moment.

Um, because crisis, I mean, there's a long history of, of framing, uh, immigrants like my parents and others as part of a threat to our national identity. I mean, this, this has everything to do with immigration laws, um, enforcement policies, all of that. And then also just the ideologies that come with it. You know, the, in the seventies people started talking.

In the eighties were talking about the brown invasion. [00:08:00] Mm-hmm. Um, and so that's the crisis. It's a shift in the order of our identity, our polity, who we are. So I refrain from all that language. 'cause it's, it plays on ethnic racial stereotypes about, and like anthropologies and like, what people are in the world is, oh, this person is a threat.

They are instigating a crisis instead of, you know, as Christians we say no, like human beings are images of God. Like that's our language to describe each other, given by the Bible. It's like, oh, when I see you, you know, you give me another glimpse into the mysteries of God. Mm-hmm. Um, so there, or that we are gifts for one another, you know, that, that God has given us, this world is full of good gifts and when we receive each other, we receive, uh, gifts that we need for, for life, for making life happen.

So, so yeah. So language like that, I, I, I, I refrain from, from. Immigrant crisis [00:09:00] invasion stuff. I mean, I talk about it in the book, but I don't, I don't use those to say like, Hey, this is, this is what we got going on, on our, uh, uh, on our hands.

Andrew Camp: No, you're asking people in a very roundabout, subversive way to consider, and you even say this towards the end of your book, that like, we need to ponder and consider what world we live in, when the best option for people is to leave their ancestral homes and risk everything at the border.

Um, you know, and that's, you know, that invites a different conversation than, um, you know, a brown invasion like the language. Yeah,

Isaac Villegas: I would. No, thank you. So, yeah, and like you, basically, that is a quote you just memorized, so thank you. That, that means a lot to me. That was, that was amazing. Um, but yeah, I mean, that was from my, that's part of the, the story I, I told at the end there of, um, volunteering at the migrant shelter.

And Tijuana, Mexico. It's run by the Scalabrine order, uh, Roman Catholic Order of priests. They've been there since the [00:10:00] eighties. And yeah, I was there and I met this woman who was, or is Mayan, um, from, uh, Guatemala. And we, yeah, just like think she, oh, she was very pregnant. That was the part about it. Oh, that's right.

She was very pregnant and the, the shelter was thrown, thrown a baby shower for her. Um, mm. And I was volunteering in the, the closet, the, the don where all they had all the donations for, for clothing for folks. And I was asked to put together, find some like onesies, like baby wear, basically for, for the baby shower for, and it was just striking this moment, I'm just like.

This woman, she didn't wanna leave her home like, this is like your, her ancestral home. This is like her people, her identity. But because of long histories of economic exploitation, uh, related to, [00:11:00] uh, I mean we could get into detail, but like basically that US corn markets flooded, um, Mexican markets and drove.

You know, ancestral people lands. It just didn't make any sense. They couldn't, uh, grow and sell corn cheap enough, right. To make a living 'cause of us corn, which was artificial. I mean, this is all, this is not like a, this is not a free market thing 'cause it's all related to the United States and tax policies.

Basically it's, it's artificially low is what ended up happening. And yeah. So it like drove her. I mean, she can't support herself. She can't support her community. So people, what are you gonna do as you, you're giving birth to a kid? Like, I mean, come on now. Like, you just wanna survive. So obviously you move and this is not something new.

Actually this is something that has happened since, I don't know, Adam and Eve had to leave the garden. Right. Go east of Eden. You know, like we're, yeah, we are people who move. That's just what it means to be a human being. We move for 'cause of war because of, uh, [00:12:00] family issues, because of exciting opportunities and.

That's just who we are. And, and here's this woman risking her life at the border with a child, an unborn child, um, because she had no good options.

Andrew Camp: Right. And yet in this shelter, um, the community rallies for her and throws her this beautiful baby shower. Uh, because in the midst of this devastation, I don't think there's another word I can think of.

Like there people still want to celebrate life Yeah. And uphold the beauty, um, right. That is coming together, you know, and, and having a party.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah. Right, right. Yeah, exactly. And part, yeah. Cel and celebrate. I mean, this is, you know, uh, uh, in the United States, a country where a lot of Christians are all about, um, you know.

Uh, [00:13:00] providing a life, society for the benefit of unborn children or whatever, you know, like to be for the unborn, that their lives are valuable. And here's this woman who is like, no, because of us immigration policy being like, no, you actually, you're on board child. We could care less. Yeah. Might as well die in the desert.

You know what I mean? Mm-hmm. Like, it's just, it's harsh and Yeah. And in the midst of that, it's despair. Like it is depressing. It's horrible. And like you're saying, and here's a community of immigrants from everywhere. I mean, there's people there I met from like, Syria, um, from, uh, where else did I, oh, Somalia, uh, Ecuador.

I mean, it is just like people from everywhere and they're like, Hey, look, we take care of each other, right? We care for people. Like, this is what we are a community of care. You're somebody that, they're having a baby shower. That's awesome. Let's do this. You know? Yeah.

Andrew Camp: Yeah. And it's, it's this idea of solidarity, you know?

And I think it's a word that like. I hadn't thought too much of, but it's a word that in the past couple months in, [00:14:00] in the conversations I'm having on this podcast, like solidarity just keeps coming up as a word that we need in this time because I think it conveys something other than, um, donation or mm-hmm.

You know, charity case. Um, and so why, why is solidarity an important word for you as you think about migrants and immigration?

Isaac Villegas: Yeah. Yeah. So I start with, uh, start the book with this quote that just has stuck in my mind ever since I read it. Read it from, uh, Dorothy Sole, who is a, she was a German theologian, Lutheran theologian and activists.

Really thinking through, uh, life in Germany as a Christian. Uh, post Holocaust, like in the legacy of Pol, what does it mean to be a, a German mm-hmm. Christian. And she just write, I mean, her whole life is wrestling with political theology, what all of that kinda stuff. But at the end of her life, um, she, as she was dying, she wrote this [00:15:00] small book called, uh, the Mystery of Death.

And in it, there's this phrase, or the sentence she says, where, um, she says The best translation for Agape is in English is solidarity. Mm-hmm. Um, and that always stuck with me. You know, like this sense of agape, this, this love that God has for us, for the world that we are invited into. What it looks like on the ground is solidarity of joining lives with each other, to sustain each other, to care for one another.

I mean, you know, it's just like loving our neighbors as ourself is basically what solidarity is like as, and, and thinking that through in terms of what it means in our, in the midst of communities who are building bridges between immigrants and non-immigrants for, uh, community together. And then thinking about the incarnation [00:16:00] that God becoming flesh as a kind of migration story.

Um, that's, you know, the title of the book, migrant God is like, yeah. That God, uh, became human being to be close to us, to be one of us. That's solidarity that yeah. Migration story that crossing the border between heaven and earth, um, to get as close to us as possible because that's just, God can't, you know, that's just what God does.

Yeah. Huh. So that thinking about immigration or thinking about the incarnation as God's, um, migrant story as one of solidarity.

Andrew Camp: Wow. No, I love how, yeah, like the best definition for like the agape love is solidarity, which I think there's a lot to ruminate on. And then to realize the incarnation is, is a migrant story.

Um, which, you know, for some evangelicals might be a hard pill to swallow. Like it's just a different, you know, it throws a [00:17:00] curve into what, how we talk and think. Um, but he left a place and joined us, you know, and, and if our worst place, you know, like, um, you know, and then we're just past Easter, he descended into hell, like whatever that means.

Like he, he, he went to the pit of hell to, so that we could be free. And so I think, what does that mean for us as Jesus followers then to live a cruciform life, um, to follow Jesus into those pits.

Isaac Villegas: That's great. I actually hadn't thought about that. That, uh, Jesus's descent into hell. It has a part of the migration story.

That's great. Um, it makes me think of another, um, theologian that comes to my mind. Iska uh, Jurgen Moltmann in his book about the coming of God is, it's an eschatology about the end time, about the end of the world, about the purpose of life. And he think he [00:18:00] thinks very mu thinks intensely a focused way about death.

Mm-hmm. And he's, his reading of Jesus's de death on the cross and descent, uh, to the dead, to is that, um. In Jesus's death, in Jesus's dying, he becomes brother to all who are dead and dying. Hmm. So it's this other layer of solidarity there that you're talking about. Yeah. Yeah. I hadn't thought about that.

That's good. I like that. But, but the evangelical bit though, like I grew up evangelical Christianity and I still remember the song. I mean, they're still formative for me, but, uh. I remember, I don't know what the song is called. It'll come to me, but, uh, the line goes, you came from heaven to earth to show the way.

Sure. Yeah. Lord, I'd

Andrew Camp: lift your name on high. Right. You like,

Isaac Villegas: I lift your name on high. Yeah. That's it, right? Yeah. I mean that is, that is it. That's what I'm talking about. That's what we're talking about here, is that that is a, [00:19:00] my, you came from heaven to earth to show us the way, like that is a migration story.

And then Jesus says, return to the, uh, at the right, to be seated at the right hand of the father. Another part of that migration story. And that, uh, he will come again. Another part of that. It's like crossing all the time. Yeah, yeah. Right. He's crossing all the time, crossing that border all the time. Hmm.

Andrew Camp: Wow. Um, and as we were talking about death, like there was a story in the book that you shared and I think it was impactful for me living in Arizona because you share the story of this town of Eloy. Have you ever been, been there? No, I've not been there yet. I've been there. You've probably driven, driven by it maybe.

I dunno. Probably. But like, can you like. It is such a create, like, and you talk about how, you know, coming back to the idea of language, like speaking something into existence. Yeah. Can you share that story just because I, it, it, it's devastating, but also like it paints a picture of what, where we are.

Isaac Villegas: Right.

And it's one of these things that happened where I, I was just like, man, you [00:20:00] can't make this up. This is failed. No. So yeah, so Eloy based, so I grew up in Tucson. Uh, I would drive to Phoenix all the time for soccer, basically soccer games and soccer tournaments. And so, um, the stop, it's not even a stop, there's like a sign on the way to Phoenix as you're not quite into town, uh, for the town of Eloy, spelled ELOY.

And it's in, you know, kind of a dry agricultural area. Very desolate. Um, never thought twice about it. And then later on I got to know this group in, in Tucson called, uh, Mari, and I think, I think they changed their name now. I mean, Mari Es is, uh, butterflies Without Borders. Yeah. And it's a prison, it's a prison detention visitation group.

And so they, you know, once a week go visit detainees in the immigrant [00:21:00] detention center in Eloy. Um, and the Immigrant Detention Center is operated by a private prison company, um, company called Core.

Uh, no, that basically Jan Brewer, back when she was governor, started uh, inviting all these private companies to build, uh, these prisons to, because she was influential in passing very, um, immigration laws and immigration enforcement so that she knew that there was gonna be a population for this and that you can make money off of that.

So these private prisons emerged and it's, you know, like prisons are just tough in general, bad places, hard but public or like, you know, federal or state owned facilities. There's some public scrutiny, um, public, it's taxpayer dollars, all of that kind of stuff. There's, there's a setup to help hold people accountable, [00:22:00] whereas private prisons, you don't have that.

Mm-hmm. And so it is just like a horrible place. So we would go there, meet people. And then I was just thinking in my mind, like, Eloy, that's an interesting word. What's this? How, where does it come from? And I was talking to somebody about it, doing all these trips, and they're like, oh yeah, it's there.

There's this legend around here about how the, the name came to be, uh, is when they, when they had the railroad when Stop Between Tucson. I think it was between Tucson and Yuma. That's what I was told. But I don't know. Um, I did research on this and everyone talks about it as being a legend, but no one, no one, there's no like, origin story.

It's just a legend. But, but basically, so the, the a, a train conductor who's new to the route, there was a train stop in the middle of nowhere. And it was his first time and they stopped this outpost and he looks out and it was completely desolate. And then he just quotes to himself out loud and he says, uh, [00:23:00] Eloy, Eloy Lama hanani, which is the words Jesus says, um, there on the Cru.

My God, my God. Why have you forsaken me? Right? So it's included in the, in the Bible story. So this, this desolate landscape gets named Eloy as a site of crucifixion. As you know, this is what Golgatha looks like. These are Jesus' words from Golgatha. And that's what that prison seems to be. It's a place where people are just brutally subjugated.

Mm-hmm. So that they, uh, what's called self deport. So self deport. So all these are people who have, so if you're detained. It's not because, it's not necessarily because you, um, you broke a, I mean, actually I was gonna say you broke a law, but it's not necessarily that you broke a law because to cross the border isn't, is not a, um, criminal offense unless you do it a second time, then it's, then it's a criminal offense.[00:24:00]

So some people are definitely, that's their offense crossing the border. Yeah. Um, but, uh, what ends up happening is like they have, you have to, the government presses charges and then, so you have a day in court and that takes a long time. 'cause the federal government does not fund, uh, um, judges, they do not like put enough judges out there.

So there's a backlog. So you could be waiting for your case for like a year, for two years, you know, and it's sometimes an asylum case. And, um, the Trump administration at the first time and now, uh, didn't want people to wait that long. So when they would get arrested, even though they had a court date.

They would make life miserable for them by putting 'em in this detention center. So they would be like, look, I just can't handle this anymore. Just send me back to my country. Right. That what's, that's what's self deport. So part of the whole point of these detention centers is to make life hellish right.

For people. [00:25:00] Um, yeah. And I met a guy in there, I mean, I met a bunch of people in there, but this one man just told, told me a story about how he gets shifted from prison to PRI detention center to detention. He's been in detention centers for three years. 'cause he just refuses to self deport. Hmm. And he has mental health diagnoses and people don't give him the right meds.

So it gets, he acts out and it makes life, makes it even more difficult for himself. But in conversation he also told me that. Um, over the past, I can remember like three or four months that there were three people who, uh, committed suicide, who died by suicide there in the prison because life was so bad and it's just heartbreaking, you know?

Yeah. Like, absolutely heartbreaking. Anyhow, so that's Eloy. It's the place that feels abandoned. Um, and people abandoned by the law, abandoned by oversight. Um, [00:26:00] oh, but I mean, and so this is like, I'm just gonna keep on talking until Yeah, no, no. Like it's, it's,

Andrew Camp: it's heart wrenching and Yeah. Like, no, but the stories are important.

Like, again, it's keeping our focus on the, on the stories and on the real humanity of these people.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah. But this man, so the, the, the, you know, like, just so he Yeah. Get a glimpse of what the kinds of stories that I, that are stuck in my head that I shared in the book, right. Is, uh, that this man, he's telling me all this, and I'm just like, how in the world do you, like, how do you keep going?

You know, like having, like, so there's this saying, um, among, um, subjugated people, I mean, I've heard this saying in, in various places among people where like the state or whatever political apparatus is trying to get rid of them and them just remaining is part of resistance. And so the, the phrase is, um, existence is resistance.

Oh. And so like, [00:27:00] I thought about that with this, with this man there. So I'm just like, just his existence here is a form of resistance. Like, yeah. Um, and so I was like, how do you do it? How do you exist? How do you stay? Like how, how do you have the strength to do this? He's like, oh no, we have to invent little things to keep us, to keep us going.

And so he'd shared with me, and this was a i'd, I'd gone there. Basically, I went to Tucson to visit my parents, and when I go there, I've tried to go, uh, for, for Christmas. Yeah. And then I tried to go to the detention center, so it was right after Christmas. And so I asked him, you know, how he, what he does to sustain life.

He's like, oh, let me just tell you what we, the most exciting thing we did. She's like, so do you, um, do you make tamales for Christmas? And I'm like, yes, we do. I mean, that's because my mom is Costa Rican and so we make Costa Rican tamales. Mm-hmm. Um. And that's part of our Christmas tradition. Yeah. The day before Christmas.

And so he was like, yeah, well I grew up making tamales for Christmas too. A lot of us did. Uh, but they're Mexican tamales. And so this is like a, this is [00:28:00] actually just a friendly, um, uh, argument among various kinds of Latinos where the, we all swear that our version of the Tamal is the right one. Yes, exactly.

So for him, like it's the corn husk tamala. Yeah. And mafar me, it's banana leaves for us. Anyhow, so yeah, we're talking about that, but I'm just like, how in the world do you make the a in here? Like what do you do? Like that seems impossible. Yeah. So it's like, oh, this is what we do. We save up money that all of our family and friends send us from the outside.

And then we, um, buy Dorito chips from the commissary on the inside. And I'm like, okay, Dorito chips. So he buys Dorito chips. And so this is a bunch, you know, like a group, I don't can't remember how many of 'em, but like him and his friends, so like maybe four or five people. Uh, so they pulled their money together.

Buy Doritos, and then they mash up the Doritos and that's the masa. And then they add water in it. Yeah. And that's the masa. The, Hmm, what is masa, how do you translate Masa? I don't even know. Corn. Like it's a corn flour. Corn flour. Yeah, it's a corn flour, like, um, [00:29:00] like bread, like it's a grainy bready substance that you're gonna bake, basically.

Yep. Yeah. Um, so that's where the Masa's Dorito chips with water in it. Pulverized Dorito chip. And then for the filling, it says that they, at the commissary, they sell, uh, overpriced, uh, pork product, not quite pork. Pork product has no idea what's in it. So they buy pork product. And so that's the filling.

And uh, then for, you know, they don't have banana leaves, nor do they have, uh, um, corn hus. Yeah. So for the wrapping, they just like use plastic trash bags as they cut these big rack rectangles. Oh my goodness. Wrap it all up and cook it in the microwave. They have access to a microwave in the, uh, common area.

Yeah. And, and he was just like, that's, that's our celebration. It's worth it. And so I was like, how much money does this cost? And he was just like, $80 for, oh man, what was, I can't remember how many tamales there was. Yeah. But you know, just enough for them. Right. [00:30:00] $80 for tamales. And that's how he, he, he is just like, yeah, we survive on like $80 tamales once a year and, you know, friendship around the table in prison.

Right. Ugh. But it was just this moment of solidarity, like going back to that. Like I even in the midst of that kind of despair, people figure out ways to care for each other, to sustain each other's spirits. Where a meal becomes like food for the soul. Right?

Andrew Camp: Yeah. No, and hospitality and meals is, is we've woven throughout your book, um, and you even mentioned this idea of a spiritual political hospitality.

Um, which you write. It's to invite their spirits to occupy our minds and enlist our lives in the stubborn hope for a world that doesn't yet exist.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah.

Andrew Camp: You know, and how, you know, and then you also mentioned that Jesus's cross points us to all the crosses mm-hmm. In the rest of the world, which I think is that invitation to remember something.

Yeah. Uh, despairing. And so like what [00:31:00] help, help us understand how hospitality first as this spiritual, political idea and then the actual hospitality, how have you seen it operate throughout your ministry?

Isaac Villegas: Mm-hmm. Yeah. No, thank you for those, those are really good. Uh, but yeah, so the first point about the spiritual political act of remembrance and table fellowship.

Yeah. That's where I was thinking about what communion means. Hmm. Um, and how the communion practice of the church, you know, the words of institution in, uh, first Corinthians 11 where Paul says, you know, you know, these words have handed on to me and hand on to you, and there's a line, you know, which I say, you know, when we gather for, uh, communion, um, the Lord's table is, uh, as often as you eat the bread and drink from this cup, you proclaim the Lord's death until he comes.

Mm-hmm. Again. [00:32:00] And so this sense of like this communion practice, which has been the central practice of the church from the beginning, I mean, well, maybe baptism too or kind of the two, like right. You gotta initiate people into the fold. And then there's the what sustains people, which is communion. And so like, this is like fundamental to our faith and it is about our posture towards somebody who was killed, you know Jesus. Yeah. Which is so like you proclaim the Lord's I, so I Mennonite, like, we take the, the words pretty seriously, like Bible words, pretty seriously. And we get a little ornery sometimes when people add stuff to it. I mean, I'm, I'm beyond like I understand, but it's so, yeah.

We say those words. But it's always interesting to me in other traditions where they add, replicate the Lord's death and resurrection. I'm just like, yeah. Right. I mean that I understand why we wanna do that. It makes sense. Right. But like to take seriously that is the [00:33:00] Christian posture in the world as formed by those of us who come to the table regularly is one is a posture towards a death.

Andrew Camp: Yeah.

Isaac Villegas: The crucifixion of Jesus, the crucifixion, and I mean, crucifixion of Jesus. This is a torture. You know, this is basically Roman form of torturing somebody to death. Um. Actually, that just struck me recently, this past Easter, I, uh, or Holy week, I preached Good Friday. And that image in John's gospel, the moment where after he's dead already, they have to make sure he's dead.

And you know, it says to fulfill the prophecy that his bones wouldn't be broken. They didn't like break his bone, his legs. Right. So that he would fall down and like suff ensure his death. Yeah. So instead they pierced aside and that's where the water and the blood comes out. And it, I was just thinking about that, like the mutilation of a corpse [00:34:00] like that is just absolute, that's a different kind of, it just struck me as a different kind of brutality this time around.

Maybe it's because I've been studying a bit like, um, what people do with human remains. Migrant remains in the desert. In, in, in two, in like the Sno Desert down in southern Arizona. And like how, how they're abandoned for so long there and, and just thinking about the care for the remains that right.

People in those communities are like, they go out and, and find remains and care for the remains. That that's part of what we do as human beings. We care for like bodily remains, but then just this cross where Jesus, after he is already dead, he's a corpse and you just shove metal into him. Like that's just.

The brutality. Anyhow. I'm, what were we talking? Oh, anyhow. All of that, yeah. All of that is, is is what we do at community. We remember that. Right? Like that is, that is what the event is. That's what we do together. We proclaim that death [00:35:00] until he comes again. Hmm. Um, and should, that should inform how our posture in the world to other deaths.

Right. And to other people who are brutalized. Yeah. By state violence, by our violence. Um, so yeah, that, that's, that. I think that's pretty significant. And Yeah. But about how the, the cross, how communion is a way of remembering Jesus' on the cross. His death, his resurrection, but that also turns us to other crosses.

That's, um, hopefully I give credit in the book. I think I do, but maybe I don't. And I, but, um, it's Jon Sobrino Sabr line. Jon Sobrino was of an a he was a priest. Priest. You do give credit just Yeah, I do. Yeah,

Andrew Camp: yeah, yeah, because I have it, I have that quote written down and it is, you know, I have Jon Sobrino written right next to it, so, yes.

So,

Isaac Villegas: um, so yeah, it's Jon Sobrino, and he was a, he was a Jesuit priest in El Salvador and he was part of that community where he. Um, you know, this [00:36:00] is the US uh, funding of the dictatorial regime in El Salvador. And part of these people who are trained in Fort Benning, Georgia, not far from where the School of the Americas, they trained in, uh, counterinsurgency and, and, uh, torture interrogation techniques.

They raided the, the Catholic seminary there and murdered, uh, the nuns and the priests. Uh, one of the priests was this guy, um, Ignacio aia, who was an important theologian in Latin America, and Jon Sobrino was part of that community, and he just happened to be away, like he was on a trip somewhere and all of his friends, his community were just, he came back and they're just massacred.

And so he lives his life. He develops his theology in the wake of that experience. One of the things he, he, he think he returns to throughout his, his works is this sense of like, what the cross does is it [00:37:00] turns our attention to other crosses today. Like we don't understand the cross until we can see crucifixion going on today and understand the mechanisms that are involved in our lives where we, our society, our, how we've organized our lives.

Mm-hmm. Uh, results in people's brutal deaths.

Andrew Camp: Yeah. And that's what you, you mentioned the Sonoran Desert, you know, and just you, this, I don't even know how to call it like a dead zone almost. Mm-hmm. But people in the midst of such devastation, in the midst of abandonment, you have people going and carrying crosses into the desert and pinpoint, you know, marking where people have died, you know, 'cause.

There's people keep track of this stuff. And so there are Christians who are taking crosses into the desert to make sure we remember. Yeah. Uh, and don't neglect the dead. Uh, which is Yeah,

Isaac Villegas: well, it's part of what human care. Yeah. [00:38:00] Yeah. I, yeah. So I went out with, so Alvaro Enciso is the, I tell his story. I mean, he's just one of, I mean, he is just one person among many.

But, um, he, he's a, he's a Colombian immigrant. I mean, he's been here for a long time in, in the United States, lives in Tucson. And he's an artist. He is a artist. He has an art studio. And at some point, and I can't remember off the top of my head right now, how long ago it's been, um, I wanna say his early two thousands, he was just confronted with this reality that he came to the United States at a time when it was possible, and he was pursuing the American dream, which a lot of people do.

Um. And in, and in some ways he's made that happen for himself. Mm-hmm. And then things have shifted in terms of immigration policy, immigration enforcement, the major shift happened in 94. We can go into that if you want, but, um, and so he, he developed [00:39:00] this project of art installation project as what he thinks of as, uh, and he calls it where dreams die.

And what he does is he goes out and, uh, the Pima County, which is the county adjacent to the border there, the coroner's office and the University of Arizona have developed this way of keeping track of where remains are. It's database that's available. Uh, online and they drop like GPS coordinates, uh, wherever they, wherever they find somebody's remains, and then they fill it in with all the, all the information they can.

And part of it is to, you know, like somebody in, I don't know, Nicaragua, they're, you know, brother, 20-year-old brother left to go find jobs to send money back home to support the family. Yeah. And they haven't heard from them for like months and so they just don't know if he made it. And so you scour the internet trying to find his name and to, [00:40:00] you know, if he died or, or mm-hmm.

Or whatever. And yeah. So this is a database to help people find, but Ado uses it to go out. So he makes crosses in his art studio and he goes out and once a week he puts, follows the GPS coordinates and then puts a cross. Exactly where that person died. And he, the crosses are, they're not ornate, but they're like very carefully, um, I don't wanna say decorated.

'cause that feels like too trite in some ways. Right. I don't know how to, the way he makes them is he uses, it's, it's kind of like found art. Okay. Found object art as well. So he, when he goes into the desert, you know, he stumbles across somebody's ba, somebody who's crossing their backpack bottle, um, you know, a wallet with pictures in it, you know?

Mm-hmm. Like, yeah. Um, shoes for a rubber from shoes. And he incorporates all these objects into the cross [00:41:00] itself. Hmm. And he uses that to make the cross. 'cause he considered, it considers all those objects. As he puts them together in a cross as a kind of relic, because they remember the story of people, of these people we've never met, and he thinks of them as, um, of what he's doing.

What Alvaro is doing is putting together these crosses as kind of gesturing to storylines, plots in people's lives that he would never know Right. But are worth memorializing somehow. Yeah. And this is the best he can do. Um, and yeah, people go out there with him, you know, once a week he calls this, this is kind of his devotional practice, he says.

Hmm. Um, and, and people just remember the person who, you know, a lot of times there's unidentified, you know, you just, but sometimes there's somebody's name and he puts the name Yeah. On the cross and all of that. So yeah, it's, I mean it's, you know, it's like what do you do in these sites of devastation? You can be overwhelmed and be like, wow, this is a brutal world.

I [00:42:00] guess this is what, but here's somebody, this is why it stuck at like, he's like, lodging my head as a witness. Mm-hmm. Because he's like, no, this is, this is something I can do. Like, I can remember, I can humanize people. I can say, you know, this person died here and that matters somehow and I'm gonna put my cross out here.

Um, and maybe some migrant might see it, somebody who's crossing might see it. Or maybe it might change the heart of a border enforcement agent about what they're up. I mean, I don't know. He just, he has no idea the effect of it, but it's something that's meaningful to do.

Andrew Camp: No. Right. And I love that, that it's something meaningful to do.

And so, like for us, you know, I'm in Flagstaff, you know, um, listeners are all over wherever, you know, and so like, as we think through immigration in our local context, like what. Because you also encourage that worship involves liberation. And so like, it matters for everybody. You know, like this, whatever's [00:43:00] happening in the immigration world right now, and we don't need to go into those details.

Like it, it's plastered across the news, right? Like, you know, but how do we as Christians then live in solidarity wherever we are? Like what are some ways that Christians can be involved? Or like, what, how do you encourage Christians to get, take a first step,

Isaac Villegas: right? No, that's, yeah, that's, I mean, part of, uh, early on when in the, in the book, in the bookmaking process, the, um, the publisher, the great, uh, Eerdmans, they were, they're like, all right, so what are you, what are you thinking for?

They'll cover like, what sounds good to you? And I was like, oh, you know, all your covers are great. Really like them. A lot like whatever your artists design people have. I was like, but one thing like please don't put the border wall on it because I want, like you're saying, like this is a story that affects everybody in the United States.

I mean beyond too, but I, I, I think so often when we [00:44:00] think about, uh, immigration, maybe not now because of this recent Trump administration, but before when I was writing the book, um, I wrote the book during the first Trump administration and then Biden administration basically. Um, and what. During that time at least, everyone's just like, oh, you gotta go to the border to understand it.

And I was just like, no. I mean mm-hmm. People like anywhere you live in the United States, immigrants make up our neighborhoods, especially in urban environments. I mean, not just in rural, I mean, I'm in North Carolina, what am I talking about? Like right. Farm workers, you know what I mean? Like the people who are agricultural workers who like make the, like, provide food for us.

Yeah. Um, and so anyhow, so I wanted to be like, no, let's not make this about just the border. This is about, this is about North Carolina. I, let's say, um, yeah. So I'm glad, yeah. That, that also is resonant with you. And I mean, I tell a couple stories about what we've done here. I mean, I guess maybe this is part of, [00:45:00] and I don't, it's hard to.

Uh, when this book that I've written is so much about stories, sometimes it's hard for me to, to distill into like, this is what you should do. You know what I mean? Like, yeah. Right. Yeah. It's, it's hard to, and so what I do in the book is I'm just like, well, I mean, I don't know what you can do, but this is what we did.

Yeah. And that's fair. So, so what I, what we did here, um, is we, um, I mean a couple things is one, my three things come to my mind now that I'm thinking about it. Okay. So, first we did my church where, where I was a pastor, we offered somebody sanctuary. Mm-hmm. Like we said, Hey, uh, people. Need a place to stay that's safe from ice.

We will house you at our church property and defend you like Nonviolently. We're Mennonites. Yeah. Um, and to be like, to be trained in like civil disobedience and how to keep people safe and, and we will. Mm-hmm. We'll do that. And we did that for Rosa. Rosa. Yeah. She lived at [00:46:00] church, lived with us for, for two years.

Um, I mean that's a long Yeah, there's a whole chapter on that. But yeah, basically in summary, she, during previous administrations, if you had a, uh, your case was pending, so she had an asylum case pending in the courts. Uh, the Department of Homeland Security would not honor, would not want to infringe upon judicial processes, so, or infringe upon the courts.

So they're like, look, even though you could potentially be deported. Um, we will honor give time for the courts to do their thing. Yeah. Um, and so she was left alone for this during this, um, she was, yeah, she fled, uh, an abusive partner came to the United States, um, and that, but then Trump changed that and like flagged her for deportation.

And so she, all of a, her attorney was like, look, we're gonna win this case, but we just need somewhere to, somewhere to keep her in the United [00:47:00] States. 'cause once you get deported, your case is done. Right. Um, and so we did that. Um, so that's one thing is like sanctuary and I know churches are still, um, figuring out ways to do that.

Um, this time around, around, uh, the other was with, you know, this was like a wonderful partnership among community organizing, uh, nonprofits and our city council where we were encountering people who would be like the, the main breadwinner of the household would be deported and all of a. The house needs, you still have to pay rent.

Right. And you, I mean, typically it was the case that the, there was a mother with like a kid or two. Yeah. And like, what are you supposed to do? And so we fundraised for a, uh, immigrant solidarity fund through Church World Service, our local branch of Church World Service that would just give grants for people to pay, uh, just like basic necessity stuff like rent and [00:48:00] food, basically.

Right. At the end of the day. And so that was a way to like care for people in the wake of a deportation. Like these are family, you know, these are also citizen kids. You know, it's not like these, the, the line between, you know, immigrant and citizen is just gets really, uh, fluid when you're on the ground and talking to real people and getting to making friends.

Yeah. Um, so that was the other thing is like financial aid to people who are in, in community, in our community. Um, and then the third one, I forgot. Oh, and then we, we also noticed that. And this was a national trend during the first Trump administration where, um, neighbors when they would sense ice in neighborhoods and they would start documenting them, they would typically kind of disperse.

'cause they were kind of afraid of being publicized because they, they were operating gray areas of the, of the law. And so we organized a rapid res, rapid response teams throughout the city. So that like, whenever [00:49:00] somebody would, someone would call the hotline and be like, Hey, look, there's a suspicious looking van, like pulling up along with all these cars.

Um, we're not, we're not gonna go to work. We're not gonna send our kids to school. You know, like this is Yeah. Because we're worried. Right. It might be up, might be ice. And so we would send a team out there and, you know, like just getting in the way, you know, right. Of just being like, Hey, look, we're just nosy neighbors here.

What are you doing? You, you, this vehicle's not familiar, do you, are you ice Asian? Are you federal employee? And sometimes they weren't. And that was reassuring for the people. They're like, okay, yeah, we'll, we'll send our ski kids to school, or Yeah, I'll go to, mm-hmm. My job. But if they, if they were ice, then we would call more people and they would bring friends and turns into a crowd.

And ICE at the time didn't like all of that publicity, so they would leave those people alone. Um, things feel a little bit different now. I don't know actually how, how things are right now, but, and yeah, so those are three, [00:50:00] three things that we, that we did here. Um, I would say the, the thing that comes to my mind is the most, 'cause you know, like sanctuary and rapid response teams definitely on the edge of potential arrest, right?

Yes. Like civil, and I recognize not everyone's in a position to do that or wants to do that, but the thing that I am finding right now that where people are making a huge difference, I mean it doesn't change the world, but helps people's lives, is actually providing financial aid to local nonprofits who are doing wraparound care for people who are, you know, suffering in the wake of a deportation.

Mm-hmm. Like paying, uh, for rent, like I'm saying, or groceries. Yeah. But also just like therapy too. I mean, there's a group here in. In Durham where it's just like a Spanish speaking Latino led, um, therapy group and, you know, meets with kids who are like processing the fact that their parents, parents is [00:51:00] gone.

You know, like that's so traumatic. Yeah. Um, and they need money. I mean, those, those groups need money to provide needed therapy. Mm-hmm.

Andrew Camp: No, and I just, that care and the fear of going out right now, um, my wife's a psychologist and has worked and still works with some Latinos mm-hmm. Um, in the Park City area.

Um, and you know, she's heard that people are afraid to, to leave their homes. And we've gotten emails from our school district here in Flagstaff, you know, reassure the superintendent, reassuring that like, Hey, your kid is safe to come to school. And so it's, it's one of those like moments where you're like, what, what world do we live in?

Yeah. Right. Where parents have to be reassured that their kid is safe to go to school.

Isaac Villegas: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Camp: I guess, you know, one, you have to fear, we fear mass shootings, but then also now, oh gosh. Yeah. Like, you know, like what world is, where school is no longer a safe place. Mm-hmm. Right. Um, you know, and I think [00:52:00] that needs should cause Jesus followers to think, meditate question.

Isaac Villegas: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Camp: What world do we want, you know, if we're praying God's kingdom come on earth as it is in heaven, like that's not kingdom minded politics.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah. I mean, it's just like this ba I mean, maybe it's not basic. I, I, I'm pretty like with my faith over the years, I feel like I've gotten more and more.

Simplistic. I don't know. Or maybe I should say like the things that are, I, I'm recognizing that the things in the Bible that are just so simple, take a lifetime to learn. Yeah. Um, and understand. But like that Jesus says, um, you know, it's all summed up in two things or one and a half, like one thing that's related to the other.

I mean, it depends on which gospel, which is love the Lord your God with all your heart, mind, and [00:53:00] soul, and love your neighbor as yourself and I, that just, I am learning how to do that. And it's so complicated to negotiate all the things on the ground, but at the very least, what it means is like, it's not predetermined who counts as a neighbor, like the, or that when we think about, when we think Christianly about each other, maybe I should say it that way, is, is our first.

The first thing we do is like, oh, here is a neighbor, you know? Yeah. Um, this person, they're in, they're, they're here. I see them, they're around, like, I've discovered their story. They're now a neighbor. And then the question is like, how am I neighborly to them? And I, I, I just, it's wild to me that we live in a wor, in a world, in a country where the first question is, is not like, oh, is this person a neighbor?

Or We should be neighborly to each other because that's what it means to be a Christian is instead like, oh, is this a citizen? You know what I mean? Right. It's just like [00:54:00] what that is. That is not how we think Christianly about each other and about our world. Our, our first question when we see somebody is not like the, their category, right.

Of, you know, identity of ethnicity, of race, of juridical status with the state. It is like, no, this person I. I'm on my way, you know, the, the, uh, the story of the, the Samaritan on, on the way and see somebody, like, it's not like the person has to be your neighbor because you want them to be your neighbor or you live by them, or whatever it might be.

It's just like whoever you encounter, that's your neighbor and the culdesac neighborly. Um, and we can't outsource to the state, to the nation state, to the US government to decide who our neighbor is. Like that is not the role of the government. Like, uh, as Christians, we say, no, you are wrong. You do not infringe upon our faith.

Our faith is here, are neighbors, and we care for them.

Andrew Camp: Right. And the way I, you know, [00:55:00] the way to do that is to encounter relationships. Yeah. Like, you have to be in relationship. And I think that's, that's what changed for me. Mm-hmm. You know, is when I got to know these, when I got to know these brothers and sisters, you know, and, and spent time in their home and they spent time in our home, like I.

It, it takes on a different life. Um, you know, and, um, it's sad that it takes, took that, you know, versus just the recognition that, okay, you're my neighbor, I should love you. Um, but that relationship is, is vital. You know? And until you actually get out of our comfort zone and enter into those relationships, it's, it's easy to dehumanize and to, um, yeah.

Make them the problem versus mm-hmm. No, they're actually, they actually might be Jesus to me.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah. Well, I like your, I mean, now that I'm thinking about you're, I'm saying neighboring, you just said, uh, brothers and sisters, but that's even better. I dunno. Yeah. What do you think about that? I, I was [00:56:00] just thinking about that.

I was going off about neighbors and you said brothers and sisters and I like that better now. Yeah.

Andrew Camp: And when a lot of my relationship came from, you know, church, you know, and being Yeah. Right, right. Yeah. But at the same time, you know, and I think there was a new report, um, I saw that like, you know, 60, if, you know, the immigration policies come to fruition, 60% of those deported might be Christians or something, you know, like it's a, it's a huge number, right?

Yeah. Like that, you know, affiliate with a religious faith, like mm-hmm. And so you're my brother and sister, like if you call your name, if you're, if you follow Jesus, you're, you're a brother and sister. And so, like a disproportionate of Jesus followers will be impacted if the Trump administration carries through with its desires.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah. Well that's, yeah, that's, I like that a lot actually. Um. You know, 'cause we say, I mean, I've, I grew up saying, not we, I don't know about you, but like, yeah. Um, I don't wanna [00:57:00] impose my, the Christianity that has been formative for me, but we grew up saying, you know, like some version of, you know, the significance of baptism is that, you know, our, our relationship is, it's like thicker than blood.

Like what happens in baptism is like, we are made akin to each other, like you're saying. Yeah. We are made brothers and sisters to each other, and at the very least, that means we should be involved in each other's lives and care about being separated from each other. And yeah. No. Yeah. Oh yeah. No. And so in my, in my book I do have, talk about, now I'm thinking about this is, um, I do talk about learning from my grandmother about mm-hmm.

Kind of her table. Yeah. Her table hospitality, her table pol, I mean politics, but she wouldn't use that one. But her, her form of like life around the table where she would always invite people like, you know, us grandkids, but then our friends [00:58:00] mm-hmm. She always had food for us. Yeah. And we'd be like, hell yeah.

Stop by. I have my apoyo here for you. And like her, her way of table fellowship, her posture towards the world where what it was like centered around this table and feeding people made it so that like all of our friends became by extension kind of part of her family. Yeah.

Andrew Camp: Right. Yeah. No, and I remember when we were in Park City and there was a couple, a Latino couple that if I went away for a conference, like they would always bring a meal over to Claire and, and the girls.

Yeah. Right. And, and like, and this wasn't a fa like they had. Twins who were younger, you know, like, it's not like they were, had the space or the margin mm-hmm. To provide this meal, but their way of being was just no. Like, we'll take care of your wife for you, Andrew. Like, don't worry about it. Like, we got her.

And you're like, none of the Caucasians or white people would ever think about that. [00:59:00] Sad. I, I don't think, you know, like, you know, or like, I remember we got invited to one of their birthdays and it's us around the table, and I'm the only guy that doesn't speak fluent Spanish. And so like, they helped me understand and Right.

Mm-hmm. We, you know, but like, I remember leaving that night thinking this was one of the most enriching experiences and parties I've been part of, you know, and because it was just, I, I, I, I don't know what it was, but it just, my heart was warmed. Yeah. Yeah. Uh, just being with them.

Isaac Villegas: Mm-hmm.

Andrew Camp: Um, and it just changes the way you see the world.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah. No, that's great. Yeah. Heart. You're, now you're talking, uh, Emmaus Way language and Luke. I mean, but that is the story. There is this, you know, the post resurrection story of Jesus, like the two disciples, Cleopas and his friend. Yeah. They're like, what in the world's going on? We just haul all this crazy stuff in Jerusalem.

They're walking to home to their village of, of Emmaus, and all of a sudden the stranger shows up. [01:00:00]

Andrew Camp: Right.

Isaac Villegas: Uh, who like Eavesdrops and inserts himself in their conversation. And it's in the, in Luke's gospel, the word there for stranger, I mean, it gets translated a lot as stranger. Um, but in Greek it's, uh, uh, paro and it means, um.

It means foreigner. Mm-hmm. That kind of stranger. Yeah. Like ro in Spanish like a stranger. But it's, ro is somebody who's like foreign to you. Right. Um, and you know, depending on what Greek lexicon you use, gets to find something like somebody who, um, isn't a place where they don't have documentation or, uh, don't, or have alien status or are not of that nation, or whatever it might be.

Mm-hmm. And so here's this foreigner who shows up and inserts himself in the conference. They're like, what are you talking about? And the, and CLE is just like, are you the only foreigner who does not know the things that have happened? Right. And then they recount the story. Yeah. And then they, uh, [01:01:00] this person just keeps on talking with them and chat.

And then finally it's like late and they show up at their house in, in Emmaus and they were like, Hey, look, you shouldn't walk back alone. How about you just stay with us? And so I say, okay. And so he goes inside. And then, um, my favorite part of the story is it says that they're gathered around the table and then, you know, this stranger, this foreigner takes their bread.

Right. It's so wild to me. 'cause it's not like they serve him food because they're, uh, in their house, but he like raids their refrigerator or pantry or something. I don't even know how this happens, but it says he takes their bread and breaks it for them and then this breaking of the bread, um, their eyes are opened and they see that it was Jesus.

And they say, we're not our hearts strangely warmed. Yeah. Right. Yeah. Yeah. I've heard you, you said that you heard that la you said those words and that's where Yeah, no, and I heard

Andrew Camp: you talk about that story on another podcast. Um, and just [01:02:00] love had ne it's one of my favorite stories because Jesus is recognized in the breaking of bread.

Like Yeah. You talk about somebody who wants, you know, as I think about food and spirituality, like Jesus is recognized in the breaking of bread. Yeah. But like to recognize that he is. Classified mm-hmm. As a stranger, an alien in their midst. Like that takes on a whole new, like ramifications. Yeah. You know, for, for neighbor.

And you know, you're not just talking about a, an acquaintance, you know, who was around, you know? Mm-hmm. You're talking about somebody who is from a different country. Yeah. Yeah.

Isaac Villegas: And I think what the, I, maybe the part that gets me too about it is, yeah. Again, with him taking their bread and offering it to them in their house, just thinking about the logistics, I would be so put off if somebody did that, because I really actually, I just really like make food for people and like care for people in my home and I, I get pleasure out of it.

Right. If some were to, to like interrupt my idea of what the meal should be, I would be like, wait a minute. Anyhow. But that, I think also what it does is it messes with our [01:03:00] categories of hospitality. Mm-hmm. And it counts as guests and host. Right. And how those things so easily flip around on each other and they're not as stable.

Categories as we like to think. No. Um, I mean, thinking back to Rosa when she was in sanctuary at our church, uh, just comes to my mind is like she would, she loved to cook and so she would use, we figured out like one of the ways that it was a way for her to both like, be there with us and have something to be involved in community life, something she could do.

And also in terms of like making some money, she would do this for the outside, for outside groups, but she would use our, the kitchen there at church to make papusas, which are, um, I did not grow up with Papusas because that most of the stuff that I grew up with were, was like Mexican cuisine and Costa Rican in Columbia.

Um, but it's, it's central American Masa. Uh, thick tortilla, gordita style with like [01:04:00] a filling, like beans or something and or pork in the middle. And so she would make papusas for us for like community meals, you know, for the church. And so it was just this really interesting moment where she was guest, right?

Like, yeah, tradit. I mean, we, we think about it. Our church was offering her hospitality. We were hosts, she was guests. But then at the same time, like I would go home after church. She wouldn't, she had, 'cause we, you know, converted an office space into her apartment. So it became her home. And then she would make meals for us.

So it, I was always, it was always striking to me. I'm just like, I actually don't know if I'm in coming to church, I'm now coming to her house. Right. No one who's here and she's letting us use the space and Right. Uh, but then she's negotiating us and we're all there and then like meals happen and she's making us food.

I don't know. It was just this moment where I'm just like, yeah, I, I, this is all like very strange. Everything's flipping around in my head and in my life. [01:05:00] Yeah.

Andrew Camp: Right. And that's what meals do, is it blurs that line. And I think you even mentioned it that, you know, as we think about immigration, you know, shared meal blurs the line of borders, like mm-hmm.

It, you know, the borders no longer matter. Uh, because we're kin, like Yeah. Mm-hmm. You know, and that's, you know, we're not always called to be hosts. Sometimes we're called to be guests. Yeah. Uh, you know, and to enter into their life, you know, and what, what, what is in store for me as I bring a guest mentality?

You know, and, and open-handed, you know, with the relationships versus always wanting to be host.

Isaac Villegas: Yeah. I don't really talk about this in the book, but now that you're talking about it, it is something that I do believe is in, in this conversation about immigration is that I think the wi, I think migrants are evangelists who are reminding us of the [01:06:00] gospel that we don't own our lives.

That our lives belong to God, that we live by grace. Like we do not make ourselves like despite, I mean, that's the era, that's the American mythology, is that we, we make our own lives. We build ourselves by our own bootstraps. We work for what we got, et cetera. But it's like, no, like we're born from other people.

Yeah. Uh, you know what I like quite physically, we do not come onto this world on our own. Yeah. We are made by others. We are given this life, and we are being sustained every day by people beyond our recognition. Um, I could not survive on my own, like I am made by, by others. And what, what migrants remind us of is that like, that is the Christian disposition that we are Oh man.

The, the, the, what comes to my mind, I can't remember which psalm it is, it's like maybe one in the one thirties, but, uh, the first line is, um, the earth is the Lord and the fullness they're in. Hmm. And this understanding that [01:07:00] like, no, the, the, the world doesn't belong to us. This house does not belong to me and my wife.

Right. Um, this is God's Yes. And, and at the moment where I think of it as my possession, that is not thinking Christianly. No. That like this is the place that I, that belongs to me. Um, that, you know, that's when mammon is start starting to take control of our lives and how we think about each other and our spaces and ownership and, and so the sense of like migrants is evangelizing us is this sense of like, what does it mean to be radically dependent on God so that you can live in the world and hold things loosely and to say like, look, I am at people's mercy and that's how we should all be.

Maybe, um, yeah,

Andrew Camp: that's a great word. Um, I want to keep going, but I also know like time, you know, like this is, but it's a question I'd love to sort of ask all my guests and it's one helps summarize stuff, but what's the story you want the church [01:08:00] to tell?

Isaac Villegas: Hmm. A story. Um, yeah, this, so again, this is where like all the things that I learned as a kid in Sunday school, I still realize I'm, I'm trying to understand and I have figured, but that God so loved the world.

I mean, it's basically the mission of the church is like, that's, that's what it's about. That we have this life because God loves us. Right? And, um, God, to be in that relationship with God is one where we learn to love this world the way God does. Hmm. Um, yeah, that's, I think that's the, that, that's how I, that's the message I think that we're about as Christians is to say, like, I.

God so loved the world. Yeah. Um, that's for everybody and, [01:09:00] and maybe the pro most profound. Um, the second thing that comes to my mind, it's not really like a, a mission, like a, something we need to be doing, but, but just to realize what this posture means is that moment that I'm, I'm still trying to figure out how radically profound, I mean, my words are, I'll just say the line, but it's when Jesus, uh, there sharing a meal with the, the Last Supper in John's gospel and, um, then you washes their feet.

Um, I always get a little, little weird squeamish with the fact that he washes the feet first and then eats. I'm just like, why don't you eat first and then like, mess with him? But no, no, I get it. Like, you, you wash the feet. 'cause people go, but uh, but it's when he's washing their feet and after all that.

Um, he says to them, uh, I no longer call you servants, but friends. Hmm. And [01:10:00] that maybe that the solid, you know, like going back to the solidarity, to bring it back to the beginning is that what solidarity means for Jesus is like becoming friends. So maybe it's beyond neighbor. It's like God has become our friend.

I no longer call you servants, but friends and mm-hmm. Friendship is this two-way street where we discover, you know, we're bound together in joys and sufferings, you know, um, and celebrations and heartache and all of that, but it's like a French that God has made us fr how do we become friends with God, you know?

Yeah. Like, that's wild to me. Anyhow.

Andrew Camp: Mm. Wow. No, I love that. Um, yeah. Thank you. This has been a. A treat and a privilege. Um, and some fun questions to wrap up, um, just because it's about food. Oh yeah. So what's one food you refuse to eat?

Isaac Villegas: Um, I have refused to eat escargo. Okay. I've been in, I've been in France [01:11:00] and I've been served it, and I'm like, I gotta do this.

And I just, I just couldn't do it and I felt very bad. Badly. Yeah.

Andrew Camp: Okay. Fair enough. Then on the other end of the spectrum, what's one of the best things you've ever eaten?

Isaac Villegas: Whoa. Best thing I've ever eaten.

I've eaten so many good things. Best thing I've ever eaten.

I mean, the thing that, um, where my mind is going. So ev whenever I go back to visit my family in Columbia, um, it, they, they make, it's a very simple meal. But it's like a, it's like an, it's like the workers' lunch, basically. Hmm. It's like you have time and work where you go home. Like if you're in the city, let's say, or not even elsewhere, you always go home to eat your lunch with your family.

So everyone is there eating that. So we have lunch together and it's typically like a, a sopa, like a soup, a caldo. [01:12:00] Like that's pretty basic, but the call is delicious. The soup itself. But what, what makes it the meal is that there's all kinds of like, fixins on the table. Okay. So you have like, um, you might have in the, in the soup, there's probably like a, like a chicken leg, let's say.

Yep. Some kind of chicken. Um, and then you have like maybe some starch, like a, like yucca or potato or something like that. But then you have all this other stuff that you add in, like, it might be other kinds of potato or yucca or, um, vegetables. And you just basically kind of build your own soup off of that base.

Okay. And it's absolutely delicious. It's kind, my trouble with eating really good food is that, um, typically it's like I can't stop eating it. And then the more I eat, then I, then I regret it a little bit. No, but with that soup, it like fills you up. Right. And you don't feel bad afterwards. 'cause like, oh, you just ate a bunch of soup with vegetables in it.

Yeah. Anyway, so that, [01:13:00] that's probably okay. But it's also with the people, you know, like the meals with the, and then having that people like with family and I don't know. Yeah. That's where my mind goes.

Andrew Camp: No, I'd love it. No. Uh, and then finally there's a conversation among chefs about last meals, as in, if you knew you only had one more meal to enjoy, what would it be?

And so if Isaac only had one more meal, what might be on your table?

Isaac Villegas: One more meal? Hmm.

Again, I would probably go, uh, this is very basic. It's what I grew up with. You might even know this kind of, do you know the Sonoran uh, tortilla? Like there's a partic particular kind of tortilla? I don't, in the Sonoran, like in the southern part of Arizona and then down into Sonora Mexico. Well, anyhow, so I would love a, like pretty simple bean and cheese burrito made with that tortilla, because I don't want too much of the filling to distract from the [01:14:00] tortilla to Yeah.

But the tortilla is like super thin ELAs, like very ELA stretchy. Okay. And it's always made with like a little bit of oil. So you, your, your fingers get a little bit. It's only whenever I go back to Tucson, I actually bring them back with me 'cause I can't find them anywhere else. For sure. Yeah. It's that Sonoran uh, tortilla with beans and ri with, uh, bean and cheese burrito.

Andrew Camp: Yeah. I love it. I'm so basic. No, but like a fresh, a fresh baked tortilla. Like Yeah. There's few things in life that are. Better. Mm-hmm. Uh, yeah. No, I, well, thank you, Isaac. Uh, this has been a privilege, a joy. Um, love your work and if people are interested, obviously they need to buy and read Migrant God, but, um, where else can they find you, connect with you, learn more about your writing and your work?

Isaac Villegas: Yeah, I, um, I do have a substack, it's, I think it's called Migrant God. It's [01:15:00] how the book first started. I started doing a substack. Then I'm gonna start, um, ramping up again here, uh, in a bit. So if people wanna join that, um, okay. That'd be awesome. But yeah, Andrew, thanks so much for having this conversation.

I've really enjoyed talking with you and like your thoughtful questions and I don't know. Yeah, I, I felt like I, I, I was, insights were happening in our midst. Yeah. And I was, I was very grateful for that. So thank you so much for inviting me onto, uh, your show and, uh, chatting to you about. Chatting with me about the stuff that I care so passionately about.

Andrew Camp: No, I appreciate it. Yeah, and if you've enjoyed this episode, please consider subscribing, leaving a review or sharing it with others. Thanks for joining us on this episode of the Biggest Table, where we explore what it means to be transformed by God's love around the table and through food. Until next time, bye.