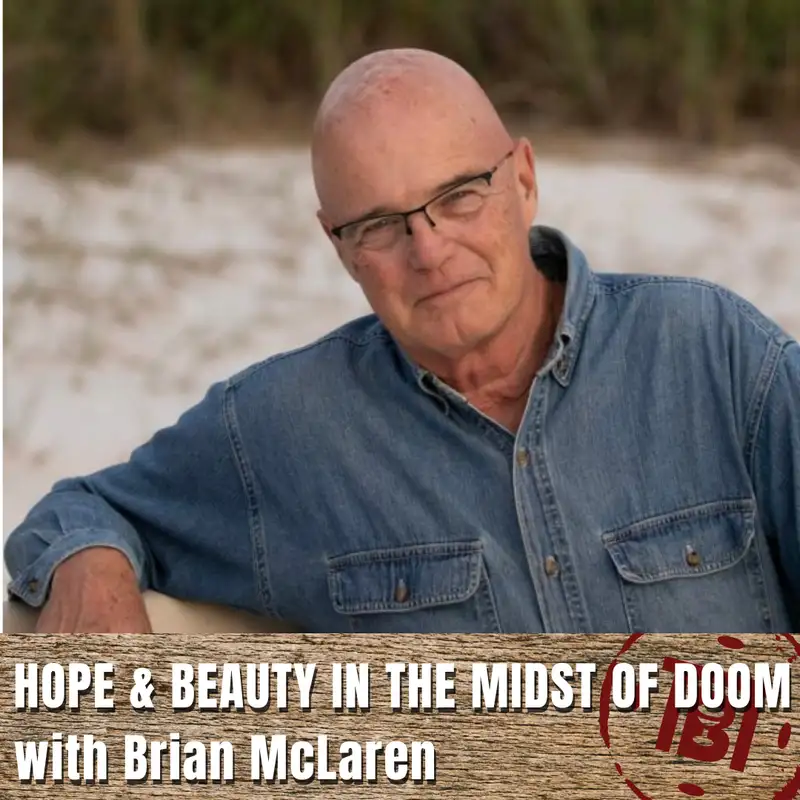

Hope and Beauty in the Midst of Doom with Brian McLaren

Episode 37 (Brian McLaren)

===

Andrew Camp: [00:00:00] Hello, and welcome to another episode of The Biggest Table. I'm your host, Andrew Camp, and in this podcast, we explore the table, food, eating, and hospitality as an arena for experiencing God's love and our love for one another.

And today I'm joined by Brian McLaren.

Brian is an author, speaker, activist, and public theologian. A former college English teacher and pastor, he is a passionate advocate for a new kind of Christianity, just, generous and working with people of all faiths for the common good. He is Dean of Faculty for the Center for Action and Contemplation and a podcaster with Learning How to See.

He is also the co host of Southern Lights. His newest books are Faith After Doubt, Do I Stay Christian, and Life After Doom, Wisdom and Courage for a World Falling Apart. His co author children's book, Cory and the Seventh Story, was released in 2023, and the first book of his new science fiction trilogy, The Last Voyage, will be published this summer in 2025.

So thanks for joining me today, Brian. [00:01:00] Um, yeah, your work has influenced a lot of us, um, and it's just a privilege to sit down and have this, uh, chat.

Brian McLaren: Well, thanks. And I'm, I'm especially happy to be with someone who likes to talk about food and tables. I think that's a good thing.

Andrew Camp: No, it is, you know, and, um, just finished your newest book, Life After Doom, um, which just the title I'm sure resonates with a lot of us in this season.

Um, even more so since, um, the inauguration of. President Trump. But this book was written before all of this. And so what, what was the impetus for a book about doom?

Brian McLaren: Yes. Well, first let me say, when I'm using the word doom, I'm using it to describe a feeling.

I'm not using it to describe the end of the space time universe or the extinction of all life on earth or something like that.

But there, there's, uh, uh, [00:02:00] Convergence of problems, a convergence of trouble, things that have been building for a long time that a lot of experts are now calling the poly crisis or the multi crisis. And by that they mean a constellation of problems like. Climate change and the larger problem of ecological overshoot and like the concentration of wealth and power among some multi billionaires who are learning how to to arrange and rig the whole system for for their benefit and and and add to that.

The increase of weapons, not only, uh, nuclear weapons and personal weapons, but all kinds of weapons of mass destruction, new ways of delivering them and so on. The spread of what many are calling surveillance capitalism, when, uh, those same billionaires have access to it. Data about us that we freely give up and some data that we don't even know they're getting [00:03:00] about us.

You put all of that together. And when you have the feeling that our problems have grown bigger than our solutions, that's when this psychological feeling That I'm calling doom, uh, uh, sneaks in and maybe the only other thing I'll say about it, Andrew, is that I'm, uh, six, I'll be 69 years old this year.

And, um, I realized that for my whole life, uh, I lived with the sense that things were generally getting better. Uh, and when, when this, this feeling creeps up your spine and says, no, our problems have gotten bigger than our solutions, it's psychologically disruptive for so many of us. So that's, that's what I mean.

I'm not just talking about the problems, but the, the feeling that we get when we start seeing these problems.

Andrew Camp: No, and I, what I love about you, you know, as you mentioned, like you're, you're turning 69 this year and having [00:04:00] been born and raised and pastored in the evangelical church, you know, I've I've been fortunate and cursed maybe to work with, you know, people of your age and a lot of them still seem naive to this general feeling that I think millennials, Gen Z, um, we carry with us just because of, we're not, we've never seen American exceptionalism, you know, we weren't through the cold war, you know, our world is, my world has been.

Just plummaged with school shootings, 9 11, like, everything. And so, like, What was the wake up call for you? How, as you know, you have pastored, taught, been around Christianity for so long, how did you stay nimble enough to come to see, see something that's worth talking about and not stay set in your ways?[00:05:00]

Brian McLaren: Yeah, well, my goodness, that's a good question, Andrew. I, I think it's happened. In many, many stages, but I suppose the first one was this. I, um, I, as a pastor, I started feeling that the theological constructs that I inherited did not really fit reality. And it was very scary. I didn't know anyone who I could safely express some of those questions and doubts, too.

Um, but when the language of a shift from the modern world to a postmodern world came up for me, it actually came in my professional life. I was a college English teacher when I was in graduate school. That's when I first encountered the word postmodern. And it was used kind of in a very intellectual sense, really growing out of literary criticism.

But the main idea of post modernity grew for me to be the critique of modernity that [00:06:00] arose after the Holocaust. And in Europe, after the horrors of World War II, European intellectuals started saying, you know, this modern world that we thought delivered nothing but progress. It's delivered a Holocaust here and it's delivered two world wars here.

Something isn't right. And then that became this kind of spillover. Then women started saying, yeah, and men have been in charge and that hasn't been so great for us. And, and with the civil rights movement in the United States and the anti apartheid movement in Africa and the anti colonial movements across Africa and Latin America.

People of color sort of saying, yeah, and white folks have been in charge that hasn't been so great and the environmental movement and it just felt like this cascade that, that, um, at every, every new wave of that cascade, white men like me had to make a choice. Do we defend the status quo or do we listen?

And [00:07:00] so, you know, some men have dug in their heels wave after wave after wave. I could not do that a good conscience. So, yeah, it, it started falling apart for me, uh, pretty, pretty quickly in the eighties and nineties. Seventies, really, into the eighties and nineties.

Andrew Camp: And so, as, you know, I'm going to guess most of my listeners have, waking up to this reality that, and carry this sort of existential doom and angst within us, like, as we wake up to reality, how do we do it in ways that aren't detrimental to our health?

Like, how do we care for ourselves? In this season where it, you know. Sometimes we wake up wondering if nuclear bombs have been set off, like, you know, like, Yes. Um, how, how do we wake up to reality without destroying ourselves?

Brian McLaren: Yeah, my goodness, that only a person who understands the gravity [00:08:00] of what we're facing would ask the question that way, but anyone who understands it would, would say yes, that's the question.

Um. And the first thing I'd say is we have to find at least one other person to talk to about it. Um, you know, sociologists have something, uh, have a term plausibility structure that when you're, let's say we're in a situation where a whole lot of people are in denial and they're fabricating a whole Kind of like the Truman Show movie, they're fabricating a dome of lies and half truths to protect a certain way of seeing and making money for people.

If you don't have a single person you can talk to, well, it's possible to survive, but it's very, very hard. As soon as we get one or two or three friends with whom we can, uh, break out of our denial and find it safe to say what we really think, once that [00:09:00] happens, I think survival becomes possible. It's interesting for me as a Christian, you know.

The that phrase and in Jesus teaching, wherever two or three of you gather in my name, one way to understand that phrase in my name means playing me like we'd say, you know, the hunger games was, uh, was, uh, you know, uh, Uh, I'm forgetting the name of the great actress in the Hunger Games, uh, Jennifer

Andrew Camp: Lawrence,

Brian McLaren: Jennifer Lawrence.

Yeah. The Hunger Games was Jennifer Lawrence in the name of Katniss Everdeen. She was playing Katniss Everdeen. And I think Jesus saying, look, if you want to play me, if you want to play my role in the world, it's really going to help to have two or three other people with you to help. And that I think is, is a starting place.

From there, I would say. We, none of us have the big picture in all of its details, but trying to get some bigger sense of [00:10:00] what's going on helps. That's what I tried to do in this book. Life after doing, I tried to have people get the best and most accessible sense I could offer of our current situation.

And then I think the third thing that could really help along with many others. We'd be getting a longer time span to think about history, and that's something else that I, I try to help people develop. We could talk more about that if you'd like.

Andrew Camp: Yeah, no, I'm curious what that longer time span is, because I think you listen to any hot takes and it's, you know, the, the urgency of the moment or, you know, we just got done with the Super Bowl.

And so, you know. Patrick Mahomes is the best ever. No, he's not now. Jalen Hurd, you know, like we're, we're, we're prone to the, you know, the latest news is the only news, you know, and without a broad swath of history. And so what, how do we get. What do you mean by having a bigger view of history?

Brian McLaren: Yes. So, let me, let me, you know, imagine you look through a telephoto [00:11:00] lens, and if you have it extended, you see far things, distant things, but a very small aperture, right?

Right. Very small frame of reference. Let's imagine zooming back to two dimensions. First, let's imagine. zooming back to just the history of our nation. Um, and so if we were to say this nation over the last 400 plus years, um, uh, involved a group of people escaping difficult conditions in Europe and seizing certain kinds of economic and personal opportunities in North America.

And it wasn't a pretty picture for the people leaving Europe, and it wasn't a pretty picture for the indigenous people when these other, uh, let's call them undocumented white European invaders came in by the boatload. And, um, uh, and then, of course, the whole epic of slavery unfolds. What you realize is [00:12:00] our nation has not been, it's been a messy, complex story from the beginning.

And, and the, the, the, uh, the beautiful society that we developed had a dark side and an ugly side. And when you get that bigger picture, I think it helps you break out of this notion that everything was fine until the Democrats, or everything was fine until the Republicans, or everything was fine until MAGA, or until the woke leftist mob, or whatever, right?

You just start to see that the terms and the categories of the current moment are very shallow and very small, and there's been a lot more going on. But if we open the aperture one level wider, I got this really from my love for nature and my interest in biology, um, in the book, I, I talk about this [00:13:00] biological concept that really has, it, it, it works in astronomy in it, uh, and, and, and in Cosmology, but it's a four stage process that's usually pictured in a kind of an infinity loop, you know, and and at the bottom left, the loop rises for a period of growth that in science, they call it exploitation.

They don't mean this in a social or economic sense, but they mean there's an energy source and there are resources. And those resources can be exploited into a period of growth. And then that growth period holds on as long as it can, but eventually the conditions change. They use up all that resource, or something changes the availability of that resource.

And then that growth phase that becomes a conservation phase, then begins to fall apart. And it becomes a release phase, or a collapse phase. And then that leads to a reorganization phase. When the energy of the whole [00:14:00] system that has collapsed now becomes a new energy source for something new, you see it with when a tree grows and grows and grows and then it falls and then the, the, the trunk decays and fertilizes the soil and more sunlight can come in and new things can grow.

It's that cyclical process. Um, and when you realize that happens in individual lives, it happens in cultures, it happens in civilizations, it happens in species, it happens in planets, it happens in epics, it, it, it, it, it, it. It happens on many levels and when we open the aperture that big, what it does is it takes our situation and says, of course, we're part of larger processes like this.

And that's good for us. I think.

Andrew Camp: No, it is good to remember that there are cycles, um, but there. You know, like you said, there are some people that, [00:15:00] you know, dig in their heels, you know, and then you talk about this death anxiety that leads to a collective neuroticism, you know, which I think can be on both sides, right?

You know, whether you're critiquing or you're trying to uphold the, you know, structure because yes. Cause you share personally that, you know, when we get angry, sometimes, you know, you found yourself in this cycle of just wanting to post anger for clickbait, you know, and wanting to gain, you know, notoriety through the, the anger and the critique.

And so like, how do we, how do we escape that and become a. You know, with with our community and hopefully with other people, like, how do we sort of embrace a more gentle cycle?

Brian McLaren: Well, let me tell you one of the ways that I'm struggling with that. I mean, I want to say that I've reached this gentle space all the time.

You know, interestingly, because I was raised in a fundamentalist [00:16:00] evangelical background, uh, I know the Bible really, really well, and I'm glad I do. I'm glad I don't have to read it like a literalist the way I was taught to, but I'm so glad I know it. Because one of the things the Bible gives us is it gives us the survival of a people through the rise and fall of many civilizations.

Andrew Camp: Mm.

Brian McLaren: Um, and so, you know, we have the The Jewish people emerging, um. Against all of these warlords, what we might call feudal lords of the ancient Middle East. And then there are these big civilizations, the Egyptian Empire, the Assyrian, the Babylonian, the Philistines, all of these different groups that come and go, rise and fall.

And even. Among the Jewish people, we see them living in very different stages. You know, we see in the very early times, of course, in the, in the book of Genesis, we see hunter gatherers, and then we see [00:17:00] agriculturalists and then pastoralists, and then we see people living in primitive cities and then larger cities.

So we see people surviving through many different arrangements and. And, and when I remind myself, human beings lived without, uh, cell phones for quite a while, people lived without electricity and people lived without democracy and people lived without, uh, you know, a court system. So, and people had some of those things and then had them taken away and they survived.

When we realized that that resilience is part of being human. And when we realize how few people have enjoyed the level of privilege and stability that people like us have enjoyed, I think we start to realize it may be our time to have to go through some of those disruptions. And And, uh, I think that helps us to give ourselves [00:18:00] permission to live in a time that's not the time that we were told was normal.

Andrew Camp: Right. Yeah. No. And, you know, when you mentioned that it may be our time, you, you talked to about the bitterness, the bitter sweetness of grief that like, yeah, out of grief, something like grief isn't all bad. And yeah. So. As, you know, you and I both being white middle class men, like, what do you mean by, like, the bitter sweetness of grief?

Because usually we don't think of grief as something sweet, but how can grief be this both and, um, you know, in our culture today for us?

Brian McLaren: Let me use a personal example and then I'll use a public and current events example. So I tell the story in the book of, you know, both of my parents died with complications of dementia.

And, um, and I, in the, in, I [00:19:00] remember with my mother, she, her dementia, she, she was so sweet. She was always a sweet person. She became even sweeter, but she just remembered less and less. And I remember there was a time my brother came to visit, uh, and, and we were with my mother. We read her a book that she had read.

She told us she liked this book that she read back in the 1930s. And we found a copy of the book. Um, and we, we sat by her bed and read it aloud to her. And it was this very sweet moment. And I don't think she remembered the book. Uh, we both knew she had talked about it was her favorite book as a child.

And we had this feeling like we held her memory more than her brain held it anymore. And it was so sad to see her go, but it was also so sweet and so precious that we could surround her bed and, and, and. And hold her memories with her and hold who she was with her, you know, there's so many [00:20:00] things like this.

I'm a very personal level. I appreciated my mother more in the process of of losing her. Um, I, I, I quote a character, a synthesized character from a TV series in the book who says, what is. Uh, what is grief but love persisting? I just think that's a beautiful, uh, idea. It's, it's love lasting longer than the thing that was loved is, is with us.

Um, now here's a contemporary example. Um, you and I are having this conversation. People will be listening when they're listening. So many other things have happened. They may have forgotten about this, but we're having this conversation right after USAID Um, is while USAID, a government agency is in the process of being destroyed and dismantled and, and lies being spread about it and horrible things being done by people who either are so [00:21:00] reckless or so dishonest or both.

That it's, it's tragic. It's, it's like a crime, right? It's like a crime scene that's happening. I was a pastor in Washington, D. C. I have many people in my congregation who work for USAID. A lot of people in the Christian community don't know that. World Vision and Lutheran World Services, many Christian organizations work closely hand in hand with USAID to do good around the world.

So I have some sense, and I've traveled in somewhere near, for nearly 40 countries, and I've seen USAID at work in, among people in need. A lot of people don't know that it was USAID, through the work of George W. Bush, spread, uh, ARVs, uh, treatment for HIV AIDS around the world. And so many lives have been saved.

So much good has been done. And [00:22:00] so in the last few days, as I've been reading about the ridiculous, idiotic, pathetic, disgusting destruction of this agency for petty, dishonest reasons. I, I'm, I'm appreciating the good they've done. And I'm, and I'm mourning the loss of it now, right?

Andrew Camp: There's,

Brian McLaren: that's the bittersweetness.

And here's the interesting thing. If I just get angry about the wrong that's being done, I am angry. I should be angry. We all should be angry. But if I'm only angry and I don't stop to appreciate the thing that's being lost, here's the thing that I'm only left with anger. But when I appreciate that people around the world develop programs to help their neighbors in, in tough situations.

The more I appreciate that as it's being wantonly, recklessly destroyed, I start to think that's what I'm going to have to do in [00:23:00] my neighborhood. That's going to, you know, we're going to have to find ways to keep that alive. That's part of the bittersweet power of grief.

Andrew Camp: Right. Yeah. Because you had this great quote that like during times of doom, people become what they never before imagined.

Um, you know, and there is that for better and for worse, for better and for right. It goes both ways again. Yeah. You know, like we can choose the anger and we can choose the death cycle or we can choose a more beautiful way. Um, you know, we can tell them about a dream. Easy reference, Martin Luther King's speech, you know, and so like, as we think about then living in this space, like.

One, how, how, how can we read the Bible in new, fresh ways and who are the voices we need to listen to? And then how do we then take this into our neighborhood, you know, and with people, um, you know, in life giving ways. And so [00:24:00] I want to start with the Bible because you do bring out this beautiful place of where we can read the Bible as an anti empire story.

Um, and then also listening to, you know, different voices, um, you know, from indigenous to, you know, African American to Latino. You know, and so, like, how do we read the Bible with fresh eyes?

Brian McLaren: Yeah, well, uh, Andrew, thanks for asking about that. Um, as I said, you know, with my background, I was taught the Bible.

Right. What I was also taught was a set of assumptions about the Bible. And very strict ways of interpreting the Bible. A lot of energy went into teaching me how to interpret the Bible the right way. I remember once hearing a preacher say, we all have white pages in our Bible, and we all have yellow pages in our Bible.

The white pages are the ones we never turn to, and the yellow pages are the ones we turn to again and again. [00:25:00] And I was taught to read through the Bible and there were certain verses. There was something called the Roman Road. We would extract verses in the Book of Romans or there was a set of verses I memorized.

I remember once I was a preacher by this time. Um, I was preaching a verse in Isaiah that I had memorized as a kid. I never read the chapter or two before and the chapter and two after and, and when I read the chapter before the chapters before and after, they were all about social justice. They were about caring for widows and orphans.

They were all about religious hypocrisy and how God preferred that we care for the poor that have big, elaborate worship experiences. Right? Yeah. So. Uh, what I think has happened for more and more of us is we weren't able to distinguish the Bible as a set of texts from the interpretive grid through which we interpreted the Bible.

And for that reason, many people just get sick of the Bible every time they open it, it just turns their [00:26:00] stomach because they remember the ways it was used to hold down women or to justify white supremacy or to blame the poor for their, for their poverty and so on. And so, uh, what I recommend we do is start by saying, I don't, even if I've heard millions of sermons about the Bible, if all those sermons were preached by privileged white male, uh, people from a Western background.

Um, and if they were taught by seminarians, seminary professors who had that perspective generations back, I ought to be suspicious that I'm only getting one angle on the book. And, um, and so, uh, that would be a first step. Next step would be to start listening to some other voices who read the Bible. And I'll just give one quick example of this.

Years ago, I finally [00:27:00] had the blessing in my life of having some friends who were rabbis. And I remember one of my rabbi friends said to me, yeah, we, we Jews, we just shake our heads when we hear you Christians read the Bible. And I said, well, tell me more about that. And she said, you have this thing called the fall.

You look, you need to know no Jew in history ever reads the first few chapters of Genesis and creates an idea called the fall. And I said, well. How do you read the Bible? And when, when, when she talked about the Jewish way of reading the Bible, I just realized everything that I read in the Bible is framed by a reading of the first three chapters that changes everything that follows.

And sorry, it opens our, our possibilities and we see new things.

Andrew Camp: No, for sure. And I remember I was recording a podcast, I think it was the week after the election and it was with David Swanson, who's a multi ethnic pastor in Chicago and has written [00:28:00] some great books on racism and environmental justice.

And I asked him how his congregation was doing, um, you know, and it's like 33 percent African American, 33 percent Latinx, you know, so multi ethnic and he's like, they were leaning into worship and part of them were like, we've been here before. Like, we know this story. Um, you know, and so I think sometimes surrounding ourselves with, with people who have experienced the worst society has can help us develop that resilience.

And I was like, Oh, that's a beautiful picture. Because when I'm stuck in my just white evangelical subclass or white subclass of Flagstaff, like I can't remember that other people have traveled this road before me and can offer as guides.

Brian McLaren: So important. So it's interesting. I mentioned rabbis and then you mentioned African American pastor.

If you were to ask a [00:29:00] hundred rabbis, what is the most pivotal text, a story in the Bible, they would say the Exodus, the story of the Exodus, um, in a Jewish reading of the Bible, the story of the Exodus is about God. Hearing the cries of the poor, hearing the cries of the enslaved and oppressed, and God is willing to turn upside down the pyramidal economies and power hierarchies of Egypt in order to free the people at the bottom.

Interestingly, African Americans for many generations, those who weren't trained by white, uh, you know, controlled institutions. They were taught to read the Bible through the lens of Exodus 2. The good news for them begins with the good news that God liberated slaves. Now, here's what's interesting about that.

When you look at the word salvation, as most evangelicals, for example, would read it, [00:30:00] they define it in terms of Problems like original sin, total depravity, and so on. But the word salvation takes its meaning in the Bible from the story of the Exodus. Salvation primarily means liberation. So if a young or older white person wants to get a fresh take on the Bible, try reading James Cone, C O N E, African American preacher, who reads the Bible through that lens, or try reading.

Oh my goodness, uh, Wilda, Dr. Wilda Gaffney, G A F F N E Y, um, uh, she has incredible Bible commentaries written, uh, from a fresh perspective. When she teaches the Bible, I notice things that are there, have been there all along. She's not reading into the text. She's actually pointing out obvious things that I had been trained, uh, intentionally by accident to miss.

And so, yeah, so much becomes [00:31:00] accessible to us.

Andrew Camp: No, I love that, like, of just seeing, you know, that the pivotal text in Scripture is, is liberation, you know, that God hearing the cries of the oppressed, um, you know, and I've always found it intriguing, you know, and why we don't focus on it more of just the fact that, you know, the time between the last prophet and Jesus is coming is similar to the time that the Israelites were in slavery and this.

This time of oppression, you know, and God appearing right when humanity needs to be free from oppressive systems.

Brian McLaren: And this, this is a very relevant to what we were talking about a little earlier, Andrew, because we, you know, what if we, what if, you know, someone could time travel from the future and say, Hey, look, Andrew and Brian and all of the people listening to this podcast.

You're entering a difficult time. The human species [00:32:00] is going to struggle for the next 400 or 500 years. You're going to have a series of billionaire oppressors who, um, who make sure that you play to their tune. And they're going to corrupt religion and politics and everything else to work by their tune.

A liberation will come, but it's going to take 400 years. Now, if we were told that, um, we would then have to adjust our understanding of what we're about, and, and there's a good chance in that process we would have a lot more in common with people in biblical times who, who had to adjust their understanding of what was going on in the world.

Andrew Camp: No, and so then, as we think about wherever we're headed, you know, and you outlined four scenarios at the beginning of the book that, you know, are worth unpacking at, you know, later date, um,

because we need to develop a new imagination for what it looks like to [00:33:00] live, you know, and I think that's what I've been most struck by with this podcast is like, okay, how in this present moment, how do we imagine new ways, you know, and some of it might be reclaiming old ways, you know, um, how do we then live like, you know, and obviously you, what I love too about your work is you're, you don't, you're not trying to be prescriptive.

Like you don't, you realize the limitations, like what works for Brian and Florida as a 70 year old won't work for Andrew and Flagstaff as a dad of two young girls. So like, But there are postures, there are themes, you know, and so what does it mean to be human?

Brian McLaren: Yes, it's funny how, it's funny how one of the things that a time of stress like we're going through, it forces us to ask that question in, in a new way.

One of the first things that I [00:34:00] think we realized it was really in the very first question you asked, Andrew, is that in times like these, we have to become intentional curators of our own inner life. Our nervous systems. are being jolted with an awful lot of stress right now. And, and we, we may find ourselves having sleepless nights like we've never had before, and we may feel our bodies carrying tension that we're not used to.

Um, and, uh, And so we're going to all have to suddenly take, take seriously the skills of self regulation, self care, self curation is the word I find fits best for how it strikes me, curating our own inner life. And that's where things like prayer that we used to think, you know, God has this checklist of things he wants me to do.

I'm supposed to have a quiet time. But you start to always know, let's see [00:35:00] whatever we do in these areas as what we need to do for our own well being. Uh, so for some of us, that might mean getting up and taking a walk and opening our hearts to God and, and, and, uh, and noticing the beauty of the, of the earth.

I have a little saying that when I'm feeling really bad, I go out and take a walk in the morning. I take a walk whenever, uh, many times a day, actually, but, um, And I say to myself, human beings are a mess, but the birds are being awesome. It just reminds me there are other kingdoms at work who are living well.

Um, so we have those, that work of self curation in the middle of that, I think. Is a renewed emphasis on character, what we used to call character in my religious background, that it seems like all of that has been abandoned now, but I think it was right to pay attention to character. And so I think we say, what kind of person do I want to be in the middle of this?

Do I want to be [00:36:00] honest? Do I want to be compassionate? Do I want to be generous? Do I want to be gentle? Do I want to notice the stranger and the neighbor and the other and the outsider and the outcast? And so what kind of person do I want to be? And then I think we also have to ask, how can I band together with other people?

Um, in ways that make sense, as you said, for my specific situation, and if, for example, if I were a parent with two small children, I'd be thinking, man, I need a little pod of other parents so that we can do this work of nesting and raising our young, um, in, in a collaborative way and with mutual support.

So that would be a start. Of course. It can overflow. There's areas of activism that we all find we need and want to be engaged with as well.

Andrew Camp: I love that, you know, finding that those people and, um, not retreating from the world, but like, you know, how do we more fully enter into this world, [00:37:00] because, you know, well, well, there's ugliness all over the place.

Like you mentioned, there's still beauty, you know, the birds are still singing, you know, this spring lilies will come forth from the ground, you know, again. And, um, you know, we can garden, we can, you know, do certain things that get us more in touch with, with the beauty of the earth and. You know, I've worked, I work as a wine rep, so I sell wine to various places, but, you know, we represent smaller wineries, you know, and to hear the stories of what these wineries are doing to care for the earth and to have holistic systems, you know, where they're.

Um, their carbon emissions are net positive now. Um, you know, you're just like, okay, like there's, there's still people doing beautiful work.

Brian McLaren: It's

Andrew Camp: so true. You know, and how to listen to those stories of the artists, the poets, the chefs, the vintners, the farmers who are cultivating something new and different.

Brian McLaren: I'm so, I'm so glad you say that because [00:38:00] I don't want to read too much into what you're saying Andrew, but it sounds to me like in your professional life, you meet these people, you see the good they're doing and you realize we may have different religions and everything else, but on some deep level, a level of values, a level of understanding of what's going on in the world.

We're on the same team here and that deep connection I think is one of the gifts that comes in times like these.

Andrew Camp: Right. No, it is, you know, and that's where the table, you know, where the table can tell stories of despair and doom. They can also tell stories of hope. Yes. And both are held in tension. Like, yes, um, you know, like, I had a privilege to sit down with Michael Twitty.

I don't know if you've ever been, but he's an African American Jew who writes on his identity through food, both through African American food. Slave food ways and then Jewish, you know, he talks that like African Americans and [00:39:00] Jews are the only people who are forced to eat bitter things so that they, in the midst of bitterness, they remember God's goodness.

Oh, yeah. It's one of those instances where you're like, Oh, that's That's worth sitting with.

Brian McLaren: Isn't it interesting too, I'm thinking of the name of this podcast. Isn't it interesting that at the end of Jesus life, he doesn't say, Hey, let's go start a church, let's go build a church building. He says, let's get together around a table.

Andrew Camp: Right.

Brian McLaren: And, and, and wouldn't it be interesting if moving forward, what becomes far more important. Then big institutions and so on of the past is the practices we learn to bring to the table, genuinely appreciating our food, genuinely feeling with every mouthful, our, our connection with the people who worked to prepare it and grow it and then thinking, and not only that, but.

This mouthful [00:40:00] depends on bees, on pollinators who flew from flower to flower, and this is connected to the quality of soil and the beauty of sunlight. And suddenly, something very spiritual happens to us with every, uh, with every meal.

Andrew Camp: No, and then the people we spend time with, they're no longer Ideas are, you know, facts on a page that the government sends us, but they're real people with real stories that have, you know, are, you know, again, being deeply impacted in ways I may not be right now, you know, and like my wife's a therapist and, um, she's She can, she's fluent in Spanish.

So she has some Spanish speaking clients and to hear what their inner tension and, you know, the fear that they're experiencing and that they're having to make arrangements, like, Hey, if I get deported, like, here's what I need you to do with my kids. Like those stories should break our hearts and we need to hear those [00:41:00] stories and see human faces, you know, behind the stories.

From the news.

Brian McLaren: So, so true. And sometimes what a, what a gift it is when that happens over a meal. And sometimes it happens standing at the mailbox and sometimes it happens, you know, on a zoom call or whatever, but wherever it happens, the desire. to, uh, not only the, you can think of it not only as welcoming the nourishment that comes from the food at the table, but the, the kind of nourishment that comes from genuine listening to another human being's story of their joys and of their terror.

Andrew Camp: No, if that space, you know, I always come back to Nouwen's definition of, of hospitality, of creating that free space where the other can be who they truly are, you know, and, and so it's. In the midst of doom, we, [00:42:00] we need that space, you know, we need that space where we can just exhale, um, feel our shoulders, um, you know, whether that's a walk in the woods or whether it's around a table with, with a glass of wine, um, you know, we need that space.

Brian McLaren: So true.

Andrew Camp: Where, where are you finding that space in this present moment? Like, what does that look like for Brian, um, in this moment?

Brian McLaren: Yes. Well, one of the blessings of my life is that that has become, you know, one of the most important parts of my life. And, um, so let, let me answer that maybe in three different ways because it's so important to me.

Uh, I, uh, just outside my window, um, you can see the light coming in the window here, uh, are, uh, is my yard and I have 14 mango trees in my yard [00:43:00] and, um. Uh, and we're in the mango blooming season. So, uh, my wife gets a kick out of this. I'll go out and I'm just amazed from when I go out at breakfast time to when I go out before I have lunch to when I go out before I have dinner and check on the blooms, you know, the blooms change and the buds change from, from hour to hour.

And to watch this tree being in the season to bloom and then the panicles or the blooms come out. And then I see the pollinators and sometimes I go out at night with a flashlight to enjoy watching the pollinators who are on the night shift of pollinization. And so, uh, and then. We have a giant iguana who lives on our roof.

They're an invasive species here in Florida, but, uh, he he's lived here for about five years and he lets us live in the house still, which is nice. But so we'll exchange a glance and, uh, and I've become a benign part of his life now. So, um, And, you know, [00:44:00] just the chance to step outdoors and feel the life that over 15 years of living here, I've planted every tree because when I moved here, this is a flat lot with nothing but lawn and a lot of it is things that grow and that I can eat and and so, uh, and then.

In addition to that, uh, on Saturday, I loaded up my kayak on the back of my car and went out into the Everglades. I live near the 10, 000 islands and paddled way out in the wilderness and just got to be there and feel. Uh, where I'm out of the sound of traffic and, and, uh, and sharing space with beautiful, amazing, uh, inspiring creatures.

And then, um, and then I'm also, one of my passions is trout fishing and trout live in incredibly beautiful places. So when I can fly fish, I'm looking forward to a trip with my son this summer where we're going to be [00:45:00] in a special place, uh, savoring that together. So those are sort of rhythms of my life that are, are not.

That are deeply connected to that self curation and to my spirituality.

Andrew Camp: No, I love that. And I hope you as listeners, you know, like in the midst of however you're feeling in the season, like don't retreat from those feelings, but don't also stop taking care of yourself. Um, you know, find those activities like Brian just mentioned that are life giving for you.

Um. You know, to find the beauty wherever you are located, um, because why, while there is a lot of ugliness in the world to beauty still abounds. Uh, and so, yeah, listeners, I hope you're hearing this, this tension that Brian is inviting us into of facing the ugliness, um, and being rightfully angry, but not leading that into despair, uh, but into, into ways of being more human, um, instead of less human. [00:46:00]

Brian McLaren: Andrew, I'm so glad you said that. I'm just thinking, you know, there are people who maybe have never really developed any of those kinds. They haven't given themselves permission to see this is important. Right.

And, um. And as the stresses grow, it won't be a luxury anymore. It will be a necessity. And I'm just thinking of people who will develop new, new wonderful habits from finding a place that they take a walk to and noticing it change through the seasons to saying, Hey, you know, maybe. Every other Wednesday night, we're going to invite somebody different over for dinner and just get to know them.

And simple things that we need at times like this, and that we'll be so glad we, we experimented with.

Andrew Camp: No, for sure. Um, and as we begin to wrap up, it's a question I ask all of my guests, um, Brian, what's the story you want the church to tell?

Brian McLaren: Well, [00:47:00] let me first say, um, if I could recommend people look into someone on this subject, there was a Catholic priest in the 20th century that I wish everybody knew about.

His name was Father Thomas Berry, and this was his great life's work, um, trying to rediscover our story. So I wish that we would tell a story of creation that, that, uh, we, we don't, we have many metaphors and words we use to try to describe what we mean by God. But what we mean is this creative force in the universe, this creative force that you start with a big bang.

14 billion or however many years ago, and you end up with Bob Dylan and Beyonce and Bach and Beethoven and Mozart and Jacob Collier. And you end up with painting and art. You end up with wine. What you end up with the amazing varietals of wine and you end up with mangoes [00:48:00] and you end up with, uh, birds and, and you end up with this beautiful, amazing world.

Um, and. And here we humans find ourselves in it. And then we find out that we humans keep getting ourselves in trouble. Um, and we realize that we all have to choose, uh, different leaders who we will respect to try to help us deal with, uh, this predicament that we humans find ourselves in. And I wish the church would say that, uh, that we have all found the life and teaching of Jesus to be the most important guide that, uh, that we see anywhere, and that we are seeking to, uh, let Jesus be a teacher and leader for us, not to the exclusion of other teachers, but to To get us rooted in a way or a path that then helps us be able to learn from others as well.

So that we can work together for the common good. I wish that the church would tell a story something [00:49:00] like that.

Andrew Camp: I love that. Yeah. The creative force behind this world is, um, is beautiful. Yeah. Um, and it can be subversive. Yes. And there are ways, yeah, just to embrace, embrace that. Um, especially as we, we wrestle with this existential crisis.

Um, and doom we face, uh, and then some fun questions, you know, about food since we're about, you know, I love food. Um, what's one of the, what's one food you refuse to eat?

Brian McLaren: I won't eat octopus anymore after seeing that movie, my octopus teacher. Okay. It's not like I've loved octopus before, but I just feel I don't want to eat any octopus anymore.

Andrew Camp: Fair enough. Gotcha. And then on the other end of the spectrum, what's one of the best things you've ever eaten?

Brian McLaren: So this is [00:50:00] the first thing comes to mind. Of course, I love coffee, but I remember one day I was visiting. I was visiting a friend of mine took me to stop by and see his mother, and she had some Kenyan roast coffee beans that she ground, lovingly ground and then filtered. And I remember drinking that cup of coffee thinking I have never had a cup of coffee this good before in my life.

And, and I just remember the feeling like how many other things have I never really noticed how good they could be. So that's the one that comes to mind.

Andrew Camp: I love that story. Um, what a beautiful story. And then finally, there's a conversation among chefs about last meals as in. If you only, if you only had one last meal to enjoy, what would be on your table?

And so if Brian knew he only had one last meal, what might be on your table? [00:51:00]

Brian McLaren: Today it would be a margarita pizza with some really good tomato and some really good basil. A whole lot of basil. Yeah. And that's, uh, that's what it would be.

Andrew Camp: Awesome. I love it. Uh, so Brian, this has been just a joy. Um, I love your heart, your gentleness.

Um, thank you for taking this time, um, to be on my podcast. If people want to learn more about your work, where, where can they find you?

Brian McLaren: Well, I have a website, brianmclaren. net, and there's a link to social media and blogs and books and podcasts and everything else there.

Andrew Camp: Awesome. Perfect. Yeah. And if you are looking for a book of just how to be present in this time and to wrestle with this moment, do buy, um, Life After Doom.

Um, it's not an easy read, but it's a read I think we, we need to grapple with. And so do pick up the book wherever you, you get your books. Um, and if you've enjoyed this episode, please consider subscribing, leaving a review or [00:52:00] sharing it with others. Thanks for joining us on this episode of The Biggest Table, where we explore what it means to be transformed by God's love around the table and through food.

Until next time, bye.