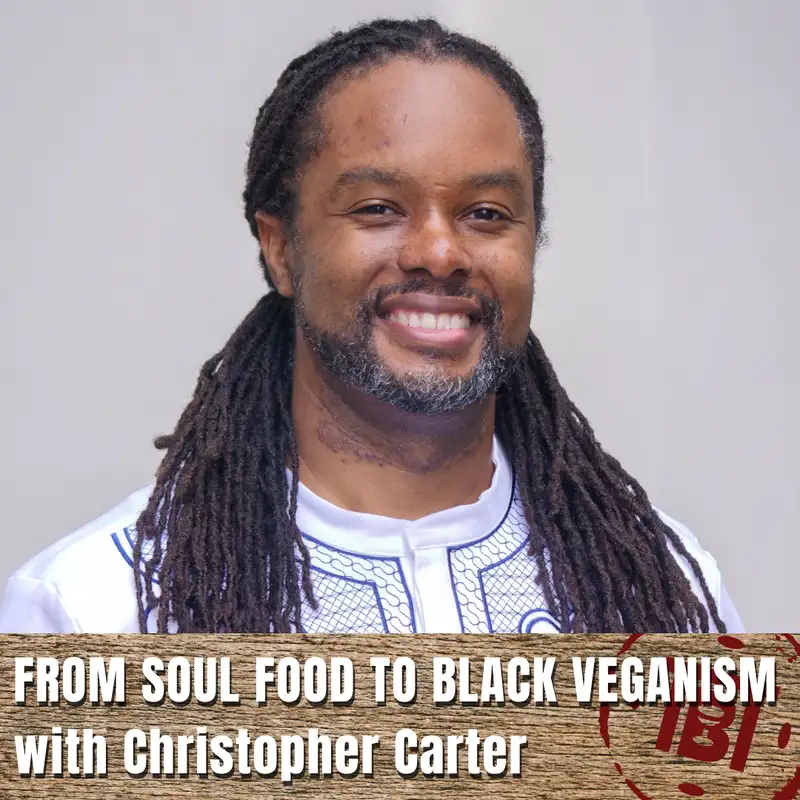

From Soul Food to Black Veganism with Christopher Carter

Episode 35 (Christopher Carter)

===

Andrew Camp: [00:00:00] Hello, and welcome to another episode of The Biggest Table. I'm your host, Andrew Camp. And in this podcast, we explore the table, food, eating, and hospitality as an arena for experiencing God's love and our love for one another.

And today I'm joined by Reverend Dr. Christopher Carter. Christopher's research, teaching, and activist interests are in black, womanist, and environmental ethics, with a particular focus on race, food, and non human animals. His publications include Race, Animals as a New Vision of the Beloved Community in Animals and Religion, The Spirit of Soul Food, and Blood in the Soil, the Racial, Racist and Religious Dimensions of Environmentalism in the Bloomsbury Handbook on Religion and Nature. In them, he explores the intersectional oppressions experienced by people of color, non human nature, and animals.

Currently, he is an Associate Professor of Theology, Ecology, and Race at Methodist Theological School in Ohio, Lead Pastor of the Loft at Westwood United Methodist Church, and he is also [00:01:00] on the Board of Directors of Farm Forward, an anti factory farming nonprofit. He is married to Dr. Gabriel Carter, a small animal veterinarian oncologist. And while their son, Isaiah, is not a doctor of any sort, he definitely believes he is more intelligent than his parents.

So thanks for joining me today, Christopher. It's great to connect. Um, really enjoyed your book, The Spirit of Soul Food. , and excited to discuss it in, um, ways that my audience and all of us can learn from you.

Christopher Carter: Oh, no, thank you for having me. Uh, I really appreciate the opportunity to, uh, you know, talk about one of the most interesting things I would say that I've, I've realized, uh, as a writer is how many people, um, after they finish a project are kind of over it. And they're like, I don't want to do anything with it.

Um, that hasn't been my experience. I think, um. I'm hopeful that I've sold enough copies that they, uh, I get a chance to do a second edition. I think I'm pretty close because, um, there's definitely more to say in, in these podcasts and these [00:02:00] kinds of conversations have helped me realize, um, and learn more about, um, what I would include that I didn't include in the, in the first version.

Andrew Camp: Awesome. Um, so as we get started, I'm curious, what role did food play in your upbringing, you know, and how did the table function, um, in who you are today?

Christopher Carter: You know, it's kind of complicated, I guess, in a certain way. So, um, I'm originally from Michigan. So I grew up in a family of, you know, people who were jobs were tied to the auto industry.

Um, Reaganomics really decimated. My home state, uh, you know, in the eighties and nineties. And so I went from having a mother and a stepfather who were financially secure, who worked for the automobile industry to being laid off, um, to just, uh, you know, by the time I was seven years old, um, my dad who really struggled with, um, Joblessness, right?

And not be able to provide for his family. Um, [00:03:00] went through a depression and started using drugs and end up having to go to rehab and went to jail. And so it's my mom and it's, I'm the oldest at that time, three of us. Um, and so we were really food insecure, you know, from time I was about 7 to 12. Um, We my most of my meals were at school.

Uh, and, you know, we, we have food at home was often food from the food bank. Uh, and because my mom was usually working two jobs. Most of the time when I ate, it was just me and my sister and my brother. Um, and And so yeah, you know, times were not easy. Uh, I think I always should look back at those times and have a spirit of gratefulness because even though there are definitely times I went to bed hungry, like I'm fully aware that could have been worse.

You know, there are people who had even less than me. Um, I'm grateful for public school, uh, food programs, probably more so than most because of my own experience of realizing how important they are. [00:04:00] Um, yeah. And at the same time, all this stuff is happening, you know, we lived at that time up until I think we moved to, we moved to Indiana, where my parents got, had their job stuff.

We moved back to Michigan by the time I started junior high, late elementary junior high, and, um, my dad's at rehab, my parents are back together, finances are a little bit better. We're still poor, but we can eat. Um, we start spending more time with my grandfather and they, my grandparents lived in the country.

They live, like I lived in, say he lived in this country and he had this, uh, garden that really was like, I mean, honest, it's like a homestead, but in his mind, it's a garden. Right. And so he's the one that I really would say I began to learn and appreciate about the nuances of growing food. Uh, cause he was a migrant picker.

So he was born in Mississippi in 1938. Um, didn't really go to elementary school, you know, um, just worked in the fields, like literally picking cotton, picking berries, just. Anything, if you read slave [00:05:00] narratives, right? Like that's what he was doing still in the, in the forties. Yeah.

Um, and so that's where I really, I think, learned to appreciate all this stuff that's tied into growing food and eating real food. And, and I don't even think I understood at the time what that was. Right. You know, so I'm in my teenage years eating food that is what we would now call organic, but I didn't have a word for that. It was just like regular food. Right. Uh, and, and so that's kind of where I would say it began, you know, really began to think more about and appreciate, um, access to food and food that was cooked and food that tasted good.

I didn't start thinking critically about it until I was in my late 20s, but I would say formatively, it was the being food insecure and spending time in the summers with my grandpa, helping him in his garden is kind of what kind of gave me the foundation for thinking theologically and critically about food.

Andrew Camp: No, that's awesome that you had those two experiences because, um, they're very, [00:06:00] um, they're very different, you know, and, um, you know, in, in, in your preface of the spirit of soul food, um, you write our food ways are an expression of our identity, a way of maintaining connections to our ancestors and our ancestral homelands.

Our food ways are personal and communal, emotional and habitual. And so as you reflect on your experience, plus, you know, as you, as you've thought about. The African American experience of food, like how does that, like explain and unpack that for my listeners just because we don't think of our food ways as ancestral and communal.

We think of it very individual or my food choices are individual choices I make, but with no connection to the past.

Christopher Carter: Yeah, I think, I think people. They believe they think that, but they actually don't. I was like, I think that's what they believe. So for example, one of the, um, the [00:07:00] idea for even that, that sentence, I remember writing that, it, it came up for me reflecting on my time in graduate school, um, and being in California, you know, so far, so far away from home, going to predominantly white institution as most graduate schools are and feeling really disconnected from my community.

Um, and back home, which was not predominantly white, uh, and, and realizing that what made me feel most like myself and grounded was when I would eat the things that I ate growing up. When I would cook red beans and rice, or when I would make collard greens, uh, or any of those kinds of things. That's what made me feel like I was connected to home, because I couldn't afford to go home.

Right? Like I literally just couldn't afford to go. I mean, graduate school, most graduate students don't have the money. Yep. And so that's what kind of laid the foundation for that that that claim is that there's a way in which eating those foods allowed me to feel a part of something [00:08:00] larger than myself.

It reminded me that this way of eating that these things I was eating that the way I. eat rice in the way I eat beans and how I cook them, I season them. All these things were passed down, um, to my ancestors and they live within me and I'm a manifestation of that and what I would do when I began teaching, right?

So when I'm teaching at the University of San Diego, teaching undergrad at this time, I'd have my students write, um, one of their projects was on a, uh, a food dish that was meaningful for them. And so often they would talk about something they had from their childhood, something their parents or their grandparents made from them.

And it wasn't about the food in terms of what it tasted like, per se, as much as it was about the memory. Right? Like it was about the memory of like what that came from and why they ate that and what they did on this particular occasion and what it meant for them. And so allowing them to soak in that memory, right?

To like really sit in that and be like, this is, this is what's meaningful about this dish. It's not, [00:09:00] it's not just that it's like. The, the food that's on a plate, it's all the stuff that goes along with it. That's what gives it its full flavor, that full embodiment to you. And so allowing people to make that connection is what I would say.

Like we all, we all are connected to our ancestors through our foods. We just don't think like that. Like we're not, we don't, we don't contemplate right over what it is we're eating to make that broader connection that I'm trying to draw when I write that sentence.

Andrew Camp: No. Yeah. Because you also, there was a sentence that stuck out that eating is a contemplative act that, um, you know, you, we are, um, connected to our past, you know, and our food does tell a story.

And, um, I think as I've done this podcast and listeners, as you've listened, I'm sure you remember this theme coming up of just the stories that are associated with the food and I think from, um, blacks and people of color, it comes up more so than say, with my Caucasian [00:10:00] guests, um, you know, and I've had the privilege of talking to Michael Twitty and his, you know, history and what his food means to him and, um, other people.

And so, yeah, I think I love that project you do with your students, or you did with your students at University of San Diego. Um, yeah, listeners, if you're thinking about it, I would just even pause the podcast right now and think about what a dish of yours that might have hold that special memory, um, you know, and what did it signify?

Who's there with you? Um, because. Like Christopher said, we are connected, and so how do we remember that and recall that to mind, uh, I think is so important.

Christopher Carter: Speaking of Michael, that's one thing I want to say, like, you know, because for those, I'm sure your listeners know Michael is Jewish, and one of the, I've gotten a chance, a few occasions to speak to Jonathan Foer, a writer who's also Jewish, um, and so in his book, uh, Eating Animals, he tells a story about his, um, grandmother.

[00:11:00] And how, why she was so concerned about what they ate is because she's a Holocaust survivor, and I had the same experience actually with the student in one of my classes, who's a great grandmother was a Holocaust survivor, but his grandmother had this dish that she prepared that she learned from her mom and same kind of memory was wrapped up in there.

Eating. And so I had them do this project where they tell this food narrative is what this project is called. It's actually, they have them record a video and do it with someone, like with their parent or whoever they're telling a story about. And so as one of my students is talking to his mom about this toast and like this kosher dish, it's like toast and eggs and stuff like that.

It's really cheap stuff, but it's more about, again, how they make it in the story that's around it. They both start crying. Like they both hadn't went into it feeling emotional, but as they start telling the story around why this dish is important to their family and why kashrut is important to their family, why they eat this way, it, it connected with [00:12:00] them.

And again, like I said, it connects them to their ancestral past that it is about taking that time to pause and recognizing that eating can and ought be a contemplative act. You know, sometimes we're in a rush and you're driving, you gotta do what you gotta do, but man, but you're at, you know. Every couple of days, man, take the time to just slow down, you know, and just really think about what you're eating and it will, it will, it will change how you eat, it changes what you think about what you put in your body and your relationship with food.

In my experience.

Andrew Camp: Right. Yeah, because, you know, what I appreciate about your book is just the, the trauma that can be associated too with our food memories, you know, and you, you talk about, and I can't remember if it was in the spirit of soul food or an article where, you know, that you've run into some young, um, black people that Hesitant to get into farming or gardening because of its association with slavery.

Uh, and so as you've thought about soul food, like, what, how is it tied to slavery [00:13:00] and, you know, how do, how have you untangled trauma in your own life to become who you are today?

Christopher Carter: It's been difficult, you know, um, soul food. I believe soul food is actually a manifestation of, like, Black resistance to, um, like, white supremacy.

Like, it's a way for us to have agency over what we put in our bodies, to name it and claim it, and to also make it taste good. And to find a way to feed ourselves that connects us to the foods that our ancestors in West Africa ate. Um. And I think that the emergence of soul food, the language of soul food started in like the 60s and it really was a way for people, black northerners to reconnect with their southern roots.

So there was always this idea of nostalgia and reconnecting to an idea of what Our ancestors ate for so many people, um, and because of that, [00:14:00] because the reason why so many of us are here is because of enslavement, right? I have a, I have a mixed ancestry, which I talk about in the book. So that's a part of my story.

It's not the entirety of my story. Um, I think that the reality of wrestling with the fact that Um, our diet is taught to an extent, the idea of our diet is tied to enslavement is difficult and some people get stuck in that space of only seeing it as slave food and saying this is an homage to my ancestors.

And what I try to do in the book is argue that slavery is a part, but it's not the part of our story, right? That's what I told those kids that you mentioned. Um, that's what I tell people who still really struggle with, um, Doing any kind of agricultural work or thinking about it that way is that part of the reason we were enslaved, the primary reason we were enslaved just because of our agricultural skill.

It wasn't like we had this myth [00:15:00] that we were enslaved because of like, Oh, we were strong. And while that's true, it was because we knew how to grow foods that Europeans struggle to figure out how to cultivate as well as we could hear. And so I have sourced literature that I cite in the book that. Talks about how there was like, how these people were, I would argue, doing capitalism well, like they would say, Oh, you're going to grow.

You're in the Carolinas and you're growing rice. Well, you want to buy an African from the Senegambia region because these are rice growing people. And so they already know how to do the work. You're going to have them do. I mean, that's just like, That's common sense right? Yeah, but we don't think about humans in that way and that's because we're not evil And so, you know, but that's what they were doing and and that's why that's why many of us were enslaved and so what I try to Impressed upon people is a way to try to take some pride in that to not just get stuck in the fact that of enslavement, but also think about farming [00:16:00] as a way to tell our story before enslavement in a way for us to continue our story after right through a process of liberation.

Um, and that takes that takes tending to, you know, I mean, For all of us who've been through any kind of religious or spiritual trauma, you know, you have to turn inward and deal with those reactive parts. Um, and, and for me, I think actually getting back into the land and growing food, um, telling these stories was a big part of that healing process, right?

Like it was really about, yeah, I would say storytelling and growing food and eating were a big part of how I began to heal from it.

Andrew Camp: To sort of get to this underlying themes, coloniality is, is the underlying theme of your, of the spirit of soul food. Um, can, for our listeners, can you explain, help us begin to unpack, like, as we think about our food ways and sort of the racist underpinnings of it, like, help us understand how coloniality Has wreaked havoc on everything.

Christopher Carter: Yeah, and I [00:17:00] think that's a great way to put it. So, in theological terms, Well, actually, you know, let me step back before I say theological terms. Let me define what I'm talking about when I'm saying colonialism or coloniality. Probably the easiest way to think about it is right now we live in a a world, broadly speaking, especially if you live in America, where, um, our lives are centered around serving institutions.

And I think A, the beloved community, the community that you see Jesus trying to create community that, um, prophets and activists like Martin Luther King argued for was the inverse. It's where institutions are at the service of life, right? We actually create institutions to help us actually live more flourishing and better lives.

Um, and that's just. Again, we live in the exact opposite world right now, uh, where we are called, you know, where we are driven by our work schedules are driven by our calendars in institutions that we fund and create with our tax dollars aren't often at our best interest. And this is regardless of where you're on the political spectrum, right?

So people will say, [00:18:00] Oh, I'm conservative. I'm, I'm for small government. Um, I'm for people being able to take care of themselves. Well, then within those communities, you still lack the infrastructure to be able to do that because economically you don't have the capital to actually take care of yourself, right?

And then you find yourself needing healthcare or whatever, and you're not have access to it. And then you have people who don't spend their money wisely, uh, or who invest in infrastructure that actually isn't to the benefit of the community. And so broadly speaking, colonialism is a way to de link sacred worth from uh, life, like literally is a way to look at life is not having sacred value. So again, theologically, what I'm arguing for is a, to take seriously, you know, the first and second creation narratives, right? You know, these are our stories that give us an idea of the value and sanctity of. Of life and we're creating God's image that that matters that God, um, created life and that matters.

And we're called to be stewards. And what does that mean if we [00:19:00] actually embody that and practice it rather than seeing human beings or seeing non human nature as commodities that can be controlled and that ought to be, um, sold in more or less in ways that actually benefit corporations. So that's what I mean when I'm talking about colonialism.

Yeah. And that, I mean, That is a, that is the logic that is used to justify the exploitation of non human nature, of people of color, um, of women, right? Like it's all about this idea that, that these things, that we become a thing that has less value, right? Or, or our value is only measured by how we contribute.

To this, you know, the creation of love for someone else. Um, and so I'm trying to unsettle and disrupt that and recognize that, you know, Andrew, regardless of how you feel about God, right? God loves you. Yeah, like regardless of how you feel and so [00:20:00] it's trying to get people to get that in their heads I'm like, no you have sacred worth even if you don't believe in God regardless what you believe God loves you And that matters now matter to how we treat each other in recognizing that we are that we are beloved And that I think more than anything probably has radicalized me And seeing the sacred worth in people that I don't even like has made me a much more compassionate person And has radicalized me to want to make sure that everybody feels as though that, um, they have what they need to live a flourishing life.

Andrew Camp: Right. And, and what I think separates your work from others that I've read, you know, from like Adrian Miller and talk to and Michael Twitty is, is your push to us to see not just the sacredness in humans, but sort of the sacredness and the beloved nature of, of non human nature and animals and that, that can, that it should inform our food ways.

Right. Can you say a little more about that? Just cause I think that is so [00:21:00] distinctive and where I was challenged most by your work.

Christopher Carter: Yeah, this is where, I mean, Michael and I have only had a few conversations, but this is definitely where we, we, we diverge. Uh, and I think, you know, it started with my ability to connect the oppression of my grandfather, uh, to the oppression, non human nature, non human animals.

And so. Um, when I was growing up and when I was a teenager, we would go down to Mississippi for our family reunion. My grandpa grew up in a community called Brookhaven, Mississippi. Uh, and so when we would drive, and my grandpa's introverted, I should say, he doesn't really talk a whole lot. Um, he, and we would drive down to Mississippi, and that's when he would start telling stories.

Like, once we got past Chicago, um, and started getting more into the South, he would talk about, Picking cotton and picking berries and all this stuff you had to experience growing up and He went through so much [00:22:00] racist dehumanization. He talks about the names that he was called and what that and how he understood himself and how he had to understand himself as having value beyond the labels that were placed upon him.

Um, and so I kind of had this in the back of my mind growing up that that people used. Um, animals and the animalization of black people as a way to justify dehumanization, right? As a way to justify enslavement, exploitation, um, hadn't really made the connection to the point where I was going to stop eating animals at that point, but it was the, the seeds were planted and it wasn't until graduate school when I began to think more critically about it.

And then honestly, it was through seeing, uh, Latinx, uh, Latino farm workers, like going through and dealing with the same kind of exploitation that, um, my grandpa did. And reading how the people who own these farms, or [00:23:00] really not the landowners, people who manage the people, how they talked about them. Again, they justify this kind of exploitation by thinking of these people as less than human, by calling them animals.

And that connection, the. The logics of race are tied to the connection of animality, like that's, that's, that's what I argue in the book, like, they're, they are tied together, the only way you can, um, make, the only way it makes sense to you theologically as a, as a Christian to say, well, I can enslave this person and I'm doing something good for their soul is to say, well, this person really isn't a person, I'm actually helping them become a person, by enslaving them, that's what, that's the lie they have to tell themselves for them to, Get over the fact that they were doing that and in so doing it really cemented this link between, um, dehumanization and racialization and animalization.

Like all these things are deeply interconnected. And so for me, if I'm going to fight for liberation, if I'm going to fight for what I would call like a [00:24:00] decolonization, so anti oppression, I have to get at the root Cause of this, the root cause of white supremacy, the root cause of colonialism, is this oppressive hierarchy that places value Not in what you can produce, right, rather than who you are as, as, as a person.

And so, I see that rather than fighting for, I would argue, a lot of people fight for equality with the oppressor, They're fighting to be a part of a system where they aren't oppressed, but they recognize that some That's that's other things can be exploited. I'm fighting for the dismantling of all of that.

Right. Um, and I believe I believe within a fiber of my beings that this is the way. That is the way of Jesus. Like, when I read the Gospels and I see this and I see the ways in which the exploitation of non human nature and exploitation of animals directly impacts the people in my community. Right?

Factory [00:25:00] farms. The people who work in those are predominantly black and brown. Where are they located? Black and brown communities. Like, like, the, the, um, ecological impact impacts black and brown people. Like, it's all right there. And so, as a black person, I don't want to be complicit in their suffering, right?

If I want to argue for their freedom and their liberation, I ought to do everything that I'm capable of, right? Um, and for me, that capacity is built into my veganism, right? I'm capable of, not everybody's capable of practicing it, or they can't practice it in the way that I do, and that's kind of why I created a different version of veganism, but it's the same kind of, for me, it's like, um, You know, my favorite, and I know you said I'm Reverend Dr.

Curtis, people probably have caught on to the fact that I use a lot of scripture and it gets a little preachy, but for me, I love the book of James. Part of the reason I love the book of James is because James, the writer of James is like, don't be [00:26:00] a seer of the word who isn't also a doer of the word, right?

Don't deceive yourselves by what you say, like actually look at what you do. And so for me, It is about action. It's about allowing your faith to move you to compassionate actions. And for me, one of the most concrete actions is to not participate in the logics of dehumanization, into the logics of animalization.

And I, I feel like that's being morally consistent. Um, and that's, that's what I'm trying to do. And that's why I make that connection. Um, because I think every person of color knows that our, that racism is tied to animalization because we've all been called an animal name. We all know sometimes, I mean, it's just that, that happens.

And, and so you, you learn that pretty young. And you set it aside because again, we all participate in it. And so you think, well, it's just normal. And that's what people do.

Andrew Camp: There was a lot there. Like, I feel like I'm going to need to relisten to this multiple times just to grasp it. And so [00:27:00] listeners, I hope you caught some, some glimpses and I love your.

you know, preach all you want, uh, right, right. Like, you know, but, but really what it is tied to is you in, in your book makes clear is that you're, you want to dismantle colonialism because you want to see the flourishing of all creation. And because if Jesus came to set the world, right, that means every.

Thing living non living is set to flourish, and that's God's vision from the very beginning. Like you said, like your work is tied to the creation narratives that we were designed. Um, I forget exactly how you put it, but we were, we were to tend and to take care of into there's a gentle care, um, you know, and, uh, and so if Jesus came to set the world, right, like that's not just humanity, um, but it's all of the ways that lead to the.

Um, dehumanization, de everything, you know, um, of, of all of nature, [00:28:00] um, and that's where it's tough, right? Because that means we have to make choices consistent, um, in light of who we believe Jesus is and what we believe his kingdom is about. Um, and you know, and, and I, I, I have to wrestle with your book.

Like I have to be like, okay, like he's pushing me, Christopher is pushing me to, to ask some questions, you know? And it's good, right? That's what we books should do, right? Like it's easy to read a book I agree with and then just, you know, underline a few sentences and feel good about myself. It's another thing to read a book that's asking me to completely change a way of being in the world.

Um, and that's your book. And so for our listeners, like in light of coloniality, in light of Jesus's coming and desire to see the flourishing of everything, like how should we think about food?

Christopher Carter: Well, that is, that's a great question, and I think, before I answer it, I want to make sure that [00:29:00] I, um, I'm sure people are listening to this and they're like, I'm an ethicist, so I'm always thinking like, okay, what's the, people are probably thinking of multiple arguments against what I'm saying.

Yeah. And so I want to be clear, I come from a family of people who were hunters. Again, as I said, I'm from Michigan. That's kind of a lot of people live there. That's kind of what we do. And my grandpa, again, growing up where he grew up, I mean, he grew most of his own food and didn't eat a lot of meat growing up cause he was poor.

So we never were a huge meat eating family. Um, but for me, I probably have less, I'm really opposed to factory farming at its core, right? If you're. From a family who lives, like, we have a friend of ours who lives in Montana. They don't buy any factory farm meat. Like, everything that they do is what they have, what they grow, and what he, what, what he hunts.

Um, I don't really have too much of a problem with that. I'm like, if that's what, because, because there's a, if you actually talk to people who hunt Many of them, not all, but many of them have a deep connection to what it is they're doing, right? Like they understand the [00:30:00] sanctity of life, like because they have to deal with the death.

They see it, right? And that changes, like if you know anybody that's been in, if you have any people in your family who's a veteran that have had to experience death, it changes you. Whether it's a human or not even animal, it changes you. And so, For those folks who are doing that work, who are actually cultivating a space of reciprocity, where they understand the value of life, um, and death, um, broadly speaking, I know that, I feel as though they're practicing their faith in a way that does value and honor God's creation because we are created to be stewards of the land and we do have to, as a species, only be evolved as we have is eating meat, because I don't want to pretend that that's not the case.

Right. What I do want to make clear is both the way in which the vast majority of us consume animal products through factory farming, there is nothing sacred about that. No, this is a terrible practice that needs to be that we need to opt out of. [00:31:00] Right. And so first and foremost, that's what I am critiquing systems that exploit.

Um, most again, I say most, and I really, I would say the majority, most hunters. don't hunt for sport and for exploitation. They hunt because they, that's how they feed their families. Um, and so for me, when I think about what a future of food can look like, um, in light of our faith commitments, it is trying to create, um, food ways that can be at the surface of life.

Um, and it's really about. Both a local aspect, which I'm sure people have already listed your podcast are thinking about it's it's it's local foods. Um, but it's also participating and like, um, what I would call, like, actually supporting organizations that, um, help that really work directly with farmers.

Right? I think often we get too wrapped up in local rather than thinking like, well, local means Maybe my community, but there may be a little bit farther out. You [00:32:00] actually can work directly with like farmers. Like, so I buy from a co op that gets from things from what I would call local farmers within a mile, a certain mile radius.

That's been really fruitful for me, right. In terms of my community. And again, I live in Los Angeles. It's a bit, um, I mean, when we're not on fire, it's a bit, it's a bit, um, of a privilege because the growing season here is like forever. Right. So I don't. There isn't a lot of things that don't have access to, but I do eat within the seasons.

Like I do those kinds of things and limit what I eat because I know this would have had to have a larger carbon footprint. So, um, so for me, it's about. Um, the way to eat in alignment with the values that I have is what I call soulful eating. And so this is practicing a kind of what I call black veganism, and I know we'll come to that in a minute.

So that's eating in a way that's very conscious of the environment and the people who grow the food. It is, um, making sure that we're promoting justice for the earth. So eating in ways that are have the least carbon intensive as possible. So for [00:33:00] some of us, maybe you have a gift of the green thumb and you can actually grow some your own food.

But more than anything, maybe you actually can encourage your religious community to participate in growing food, right? Um, and so in Michigan, I have a book, especially in Michigan, but also back east. Um, there's a friend of mine, Hebrew Brown, who's in charge of the black church food security network. New York City, these churches That use their land to grow food.

Right. And and that's like, rather than having grass, you actually can, you can grow food or you can, or your church can be a food hub. Right. That's what our church does. 'cause we, we, we are in a sit, we're concrete. Yeah. We don't, we don't have, we can't grow anything. Right. Yeah. And so, but we are a hub for people to come and get food.

Right? Hmm. And everything we do, we don't need to make. We don't make any money on it, we're just breaking even. And so, it's really trying to meet people where they are, and give them the capacity to do some work without feeling the kind of shame and guilt that I think is often induced when we talk about food.[00:34:00]

Because I think a lot of foodies, if you will, try to make people feel bad if they're not doing the things that they think they ought to be doing. And I'm definitely not trying to do that. This is not about shame, it's about participating. And a liberatory practice in a way that you are able, given where you are at times, and it's about people like me who have privilege creating systems that allow those other people to flourish so that they actually can have more freedom and capacity to participate in the world in a way that it's reflective of what they want to do, rather than what they're economically limited to.

Um, so that's a little bit of a long answer, but I think that's probably enough for me to say right now.

Andrew Camp: No. And you also mentioned the necessity of small steps that like, when we look at the big picture, it's overwhelming, right? Like we look at the systems of injustice, we look at capitalism, we look at these billionaires that have enough money to completely change the world and don't want, you know, and we can get stuck, but.

Really what's the next right step for, you know, me as a family, as a person to take, um, you [00:35:00] know, cause you also talk about, uh, what was the exact phrase? Cause it had me thinking, um, Oh, um, agent specific and context specific, um, that, you know, what's right for you at this point may not be right for me, given my personhood and my context living in Flagstaff, Arizona, where we have a two month growing season.

And. You know, we're, you know, isolated in some ways, you know, we're two and a half hours from Phoenix, um, you know, and so you're thinking about, okay, what does it look like, um, for me is very different than, you know, Christopher, who's living in Los Angeles, um, which I appreciate again, because it's easy to think, okay, I just got to adopt Christopher's model, you know, and then I can live in anti oppressive way.

And that may be true, or it may be like, okay, what, who is God called Andrew to be? You know, what's the next step I need to take for me and my family, for health and for anti oppressive living? [00:36:00]

Christopher Carter: Exactly, and I think, you know, the reason I, when I was thinking about how I would describe the practice of social leading and black veganism, the reason I thought about context specific is in Because I imagined like someone trying to ask my mom to do this when we were like struggling, right?

Yeah, we're like have on food stamps and like that would have been impossible, right? But there's also there's a way we can eat that could allow us to participate in the conversation Right that could help us think about this think about how we eat In a way that could move us closer to the liberation that we all wanted, even if we couldn't do everything.

And so I didn't want to create this kind of moral hierarchy that I often encounter again in food justice circles. And I wanted to be open to people of all different backgrounds, um, and, you know, races and everything else, and so You know, there's a friend of mine, um, Rachel Brown, who's a professor in, um, in Canada.

And one of the coolest things that I learned [00:37:00] about was she had a group of Muslim students in her class. I want to say it was last year. Her food and religion class are in my book. And they really thought about, for them, adopting You know, kind of black veganism within an Islamic framework. And they were like, what does it look like for us?

Teating ways that are anti oppressive, that are in alignment with our values. And they kind of made their own thing with it, which was like, exactly what I would want. Like, it was literally, I was like, that couldn't have asked for anything better. I was like, you don't, I don't think I have the answer. I feel like I'm giving you an answer.

But then people can add on and grow and shape that makes sense for them. Because they were dealing with the same disconnect. That I was feeling in California, because that's not where their people, their people aren't Canadian, so that's not where they were from, and that kind of connection to food and identity and spirituality that really resonated with them, and so they were able to kind of find a way to shift it so it could be useful for them and their own spiritual religious practice.

Andrew Camp: That's awesome. Yeah. Because you [00:38:00] give us sort of big themes, you know, you talk about self love, solidarity and holistic interdependence as sort of the theological framework for which to deal with this. And then, um, you do lay out three practices, um, you know, for us to move forward and for soulful eating, seeking justice for food workers and caring for the earth, you know?

And so I think if we can think about those aspects, then we can adopt an agent. Um, specific and context specific mode of being in the world.

Christopher Carter: Definitely. Because I also know like, you know, again, a friend of mine I was just texting a few minutes ago, like she's diabetic, like her diet, you know, she's type one diabetes, right?

She's always been diabetic. And so she has to think differently about what she eats, right? Then, then, then many of us. And so, you know, everybody can't do the same thing, but everybody can do something. Yeah. Um, and, and before we move on, I want to make sure that I know I've said black veganism a few times.

So I'll just spend just a minute. Kind of explaining it. Yeah. Uh, cause I'm sure people were [00:39:00] like, what is why? No,

Andrew Camp: that was my next question. Let's get to black veganism. And what does this mean for you? Yeah.

Christopher Carter: Yeah. So, um, I didn't, it took me a long time and I talk about that in the book. Like I just didn't, once I came to this realization of, Oh, wow, I don't want to be complicit in this system.

Um, I, for the most part, immediately became vegetarian, um, because I'm the kind of, my particular neurodivergence is such that I'm really committed to justice and ethics, which is why I have a degree in ethics. And so like, if I think something is morally right, I'm going to go to this logical conclusion.

Uh, and I, but I knew that I didn't have the skills and capacity to be vegan in a way that would allow me to eat. It, that, that would allow me to still feel connected to my people and my community. And so I had to learn how to do it. And so, I came up with the idea of Black Veganism as a way to, to name the kind of consciousness nerve raising process in a way to make it context specific and agent specific so people can [00:40:00] recognize that this is a veganism that is what, in academics, we call an ontological.

So it's, it's more about an idea of being and becoming rather than the practicality of being. not eating meat or participating in, you know, not wearing leather or anything like that. That's a part of it, but it's about the process. And so really what I'm trying to do with Black veganism, the idea of Black veganism is I didn't, I wanted to name something different than traditional veganism because often That's associated with like, you know, a kind of privileged, um, honestly, like all the vegans I knew prior to me becoming vegan, broadly speaking, were like white, mostly white women.

And so, and it was always done about the animals. It was always about the animals and like polar bears and stuff like that. Um, which is great. You know, again, my wife is a veterinary oncologist. Like I, I am a fan of animals, but I did not become a vegan to have anything to do with animals. It has nothing, it has everything to do with people.

Like, my veganism really is tied to my community. Um, and, and so I wanted to make that up [00:41:00] front. Built on the work of Bell Hooks, in her, in her book, Feminism for Everybody, she talks about this idea of consciousness raising. How they would have these consciousness raising groups in second wave feminism, and how they would grow to learn about their participating in patriarchy.

And I was like, that's exactly what I want, right? For us to continue to eat and learn and reflect on how we're participating in the system and how we might change and challenge ourselves and continue to grow because I'm by no means perfect. I mean, I fly in airplanes. Like I do things that in my head, I'm like, ideally, I wouldn't have to do this.

Um, and I don't like all the time. Sometimes I would do things online, you know, I'm not going to Arizona to have this conversation with you face to face. We can use the miracle of technology. Uh, you know, and so you find ways to go around it as best as you can. Uh, and so I want to have the consciousness raising.

I want to make sure people understand that by calling it black, I'm calling attention to the racialized realities of animals in the ways in which. The, um, [00:42:00] dehumanization of people and the thingification of animals is tied into how we eat animals. Like it relies on this logic that is deeply tied together.

Um, and I want to name that so when I tell people I'm practicing black veganism, um, people can ask me about it so then I can talk about it and I'm comfortable explaining this is why I eat this way. But I do it in a way that, and this is for me critical, most vegans I encountered were like, You know, um, me, I mean, they were literally just like, if you're not vegan, then you're evil.

Right.

Andrew Camp: Yeah.

Christopher Carter: And I didn't want to do that. I was like, that's not, I'm like, no, man. Like, you know, it's, it's a journey. Like everybody's on their own journey. This is why I do this. Cause I see this and it's for me. Now you eat how you eat, ask yourself, are you eating in a way that's in alignment with your values?

Right. And so then people are like, Oh yeah, I think I'm like, well, what are your values? And you start listing your values and you start thinking about how your food is. Where it comes from, how it's made, you will [00:43:00] probably find out you're not, it's not as much in alignment as you actually think. No, right?

And so this whole process, this whole, the book was written as a way for me to figure out how to eat in a way that's in alignment with my values, Andrew. That's literally what it was. That was this book. I was like, man, I gotta figure this out. Cause this is, this is really important to me. And I love to eat.

I love to cook. And so let me, let me figure this out.

Andrew Camp: Because, you know. When you practice and, you know, you, I didn't get your book knowing you were going to espouse black veganism, um, you know, and you start reading it and you start reading about soul food and we have, regardless of who we are, we have pictures of what soul food is and it's usually fried chicken or, you know.

Lots of meat are, you know, if they're collard greens, they're cooked in bacon you're practicing a different type of soul food. And so how, how does your soul food still pay homage to your ancestors without the typical fried chicken that we [00:44:00] might associate with?

Christopher Carter: And that was hard for me initially, um, to feel like I was eating in a way that was disrespectful or disconnected from my community.

I think a couple things helped. One, like I said, my grandpa grew up poor and didn't eat a lot of meat. And so while we ate meat, it was always, it wasn't the staple. I would say for us, honestly, the staple was beans and rice. Like beans and rice was like the staple thing that we eat. If someone said I couldn't eat rice.

I would have a hard time because that's like, I eat rice. Probably almost every day, um, because we were a rice family. That's where my my ancestors from from rice folk. Um, and so what I do in the book as I show that our ideas of soul food has always evolved, that at its core, soul food is about the preservation and promotion of community, and that's what it's always been about.

Like when [00:45:00] black people, you know, black women brought okra seeds and watermelon and those seeds kind of seeds in their hair. They were trying to preserve a part of their identity as they were enslaved. Yeah. And so it's always been about this preservation and promotion of a, a way for us to feel connected to our past and also give a gift to the future generations.

And so what that looks like has always and necessarily shifted over time. Yeah. It's never been the same because we eat again, we eat more meat now than we ever. Ever have. And so, the idea that my ancestors in West Africa. Fried chicken is just laughable. Like that wasn't actually true. And so we have to, again, move past this idea that soul food is this static thing from this, from the 1930s to 1960s, right?

Uh, America, because it, because it's not, it's, it's always evolved and it will continue to evolve. And so what [00:46:00] I'm trying to do when I talk about soul food is recognizing that it's, it's porous. And that it is a part of a broader conversation again. It's always about and I believe that what my to preserve and promote my community now is to opt out of systems that marginalize and oppress us.

And so it's do the things and eating ways and uplift. And so for me, that is that is black veganism. Um, and to be fair, Andrew, I had to learn how to cook in ways that, um, we're still tasting like home. And that's why, you know, each chapter of the book ends with recipes, because I want people to know, like, this was done through practice.

Like, this wasn't just this theoretical exercise, man. Like I was like, I need to figure out. Like when I, so when I do, I do, when I do these book talks, um, I did one at the University of California, Irvine, and there's this, uh, older black woman that came there and I see her getting into what [00:47:00] happens is when I do it, if everything works out, I'm able to actually serve the recipes from each of the chapters to the people so they can eat while I'm doing the talk.

That's always my ideal. So that way they, it's kind of an experiential thing for sure. This woman, she has, she plates. The food and she puts everything in these little cups and I'm just like, well, that's kind of weird. Why she got it all individually set aside. And so she's tasting all them individually.

And then when I finish, she's like, you know, something, she's like, I want to tell you, she's like, I'm from Hammond, Louisiana, and I know your people. Cause my dad's from Hammond, Louisiana. And there's, I mean, and so I was like, wow. So there's this woman there who's, who knows my people. And she was like, I was, she was like, I, I didn't want to believe what you were saying.

She's like, you know, uh, because, because the way I grew up eating is tied to how I understand myself as a Southerner, as a black person, as a black woman, she's like, but I'm eating these things and it tastes, it reminds me of the things I ate growing up. It reminds me of that community in that culture. And her, [00:48:00] Compliment her praise of my recipes.

Um, honestly, I was over the moon. Like it was more than any, anything anybody else could say, because I was like, I have done the thing I set out to do, I have this old black woman who says my food tastes like it's supposed to taste for my community. I was like, all right, I think I've, I've cracked the code now.

I feel good about where things are.

Andrew Camp: No, that's awesome. Yeah. Um, and also your book, you know, and your book is primarily geared towards your community, but you have a little excursus for the white community, you know, and so my, most of my listeners are white Christian, probably more evangelical conservative, like, and so what How does this relate to white evangelical or white Christian mainline, wherever you are on the spectrum, but for the white audience, like how, how does this factor for white people?

Christopher Carter: Yeah, no, I think that, so part of the reason that I wrote that section is, um, in [00:49:00] part because my, my father's ancestry, I guess it's from Hammond, Louisiana, but his, his ancestors are, um, Spanish. So my great grandfather or my grandfather is white. I mean, he's white. He'd be classified as white, you know, um, he saw himself as Spanish, but he's white from Spain from the Basque region of Spain.

Um, and so I always had this awareness. That I, that I am black, but that's not the entirety of who I am and, and that my relationship is complicated because my grandpa and my grandpa's family, like they were overseers, like they were the ones who were like, but you know, they were the ones running the plantation, like over the, my mom's side of the family who were the workers on the plantation.

Right. And so I have this kind of, that, that complexity is within me. Right, is what I want to say. Uh, and I think it's within all of us. Yeah. And so for me, I wrote that section to recognize that for me to heal and think about that part, it was much more about a, what I call an [00:50:00] inward turn. It is about tending to the parts of me that were reactive to learning about my complicity in systems of oppression, that were reactive about, um, and being challenged by the theology of, you know, that I was, Developing this kind of theologic anthropology of what it means to see humans as, as, as create an image of God and what does that look like to not participate in, in sin.

And so for me, like the, the groundedness of my theology in the book really emerges out of, you know, the parable of the good Samaritan. Um, and for me, I see that parable as. You know, we, I understand sin to be the failure to bother to love. Yeah. And that's taken from, from Jim Keenan, who's this Roman Catholic priest.

And I think that's so evident in that story where you have the [00:51:00] priest and the Levite, right? You have the religious people who literally Failed to bother to take the time to do the loving thing, right? They can do it. They have the, they have that and they, they opt not to, but then the person who you least expect actually takes the time.

The person bothers to see the dignity, to see the self worth, to see the image of God, right. In the person that was, um, beat up, that he'd be taken care of. And so for me, what the invitation is for people who are not. People of color is to not fail, to bother, to love, to recognize that your actions impact more than just you and impact broader communities.

And what does it look like to eat in a way that not only is in line with your values, but to take seriously the reality of your call to love your neighbor, like the greatest commandment to love God and love neighbor as you love yourself. And that self love part tend to those, the stuff that comes up.

Right? Don't [00:52:00] suppress your feelings. Right? Don't pretend they're not there. Actually compassionately tend to them like you would your best friend talking to you and that gives you the space to actually connect with others. Um, and so yeah, I'm a liberationist, you know, I come from a liberation perspective, but I have found that.

I'm able to have good conversations with people who are conservative because I think there is a lot more we have in common if we're not talking about politics, we can, we can use it. We can use to get along.

Andrew Camp: No, for sure. Right. You know, because it is, we're, we're grounded in that, you know, call to, to love ourselves, you know, and then you ask us to move into solidarity and then that holistic interdependence with all of creation, human and non human and, you know, and that's, You know, um, those three themes, you know, I think are worth meditating on and then how do we eat in in alignment with those values.

And so listeners, I hope you've been challenged by Christopher, you know, and can reflect to just, okay, what [00:53:00] does eating look like given who we believe Jesus to be? In the rule and reign of his kingdom, you know, and it's a question I'm wrestling with, and I am far from perfect. Like we, you know, our eating habits are not in alignment, you know, with, with that, you know, like we buy our meats from Sam's and, you know, Kroger right now, like, you know, and my wife and I probably need to wrestle through.

And we've had some conversations of like, okay, I've been privileged to have some amazing conversations with people on this podcast. And so like, okay. It needs to change for me, like how does this podcast more than just an intellectual fun exercise, but a way of being in the world that is in alignment with what I'm saying on this podcast.

And it's a wrestling I'm constantly doing and trying to figure out, um, you know, and so listeners don't, I hope, yeah, you're not guilted by this podcast, but that it's again, an invitation to think differently. Um, and I think [00:54:00] Christopher has done that for us today.

Christopher Carter: And I would say, Andrew, it's an invitation for you to be compassionate towards yourself.

Right. Recognizing it's a process. Yeah. Right? Like no one is, you can't, I would encourage you, don't jump into this with two feet and just start doing something because you need to learn what it's going to look like for you and for your community and for your family, um, and to think critically about it, right?

Like how to feed your family, where to get your food, how to cook. It's learning. It's a whole new way of, of. Of thinking and being and doing, but my experience is that as you take those steps, right, it gets easier and easier and easier as you continue to grow. And I would argue it's growing towards God, it's growing towards love and growing this towards this way of being in the world that's, um, closer approximation of what, uh, God love calls us to be into the world.

And so be gentle with yourself and yet continue and yet encourage yourself to continue to grow. And, and sit in that tension. Um, and I believe that's what, um, [00:55:00] that is a way for us to think about moving forward.

Andrew Camp: Yeah. Awesome. Um, it's a question I love to ask all of my guests. Um, what's the story you want the church to tell?

Christopher Carter: Oh, wow.

I think, so I am, and so I'm, I'm an ordained Methodist pastor. I've been pastoring churches, been an ordained person, For about 14 years now and when I think about the answer to this question it's informed by my experience in the congregation as a clergy person and I would love the church to tell the story of belonging.

Right, and I think belonging is deeper than including. I think that a lot of times we can tell people that they're included and that they're [00:56:00] invited to this space But they don't feel like they belong, right? Uh, when you cultivate a spirit of belonging, you create a space where people don't necessarily feel like they have to fit in to know that they belong, right?

They can come there and know they can be themselves, and yet there's just something there that holds it together, that allows us to be connected to each other. Um, and that's what I want the message of the church to be, to the world, is Does anyone want to be a place where all people feel like they belong regardless of their, regardless of what they're bringing to the table, right?

Regardless of their identity or their ability, um, that they feel as though, um, yeah, that they belong. And, and, and that is, ah, I believe Jesus. Is always challenging us to expand the table to use a metaphor the biggest table, right? like it's always about like when Jesus when he when he when he gets to the In in when he goes to Nazareth [00:57:00] and he reads Isaiah scroll and he's given his first sermon and if you were like, yeah That's great.

And then he's like, but I want to include more people than just our community. I want to include they're like, wait Wait, we need to include the Gentiles. We need to include these other people. It needs to be about us And Jesus is like, no, we need to expand the table. And that's where we meet resistance by so many people.

It's the refusal, expanding to allow other people to participate and, and be with us. And so let us continue to expand the table so it can actually become The biggest table, reflective of the title of your podcast.

Andrew Camp: Yeah, no, I love that. Like belonging is different than inclusion. Um, and yeah, that's something to, to think through.

And, um, if you're a leader of a church or whether you're, you just attend a church, including somebody is very different than belonging. And so what does that mean for you and your community? Uh, it's a great, great word. Um, and so, some fun questions to wrap up about food. What's one food you refuse to eat?[00:58:00]

Christopher Carter: Pudding. Pudding. Oh, wow. Okay. Just, it just, I have texture issues. It's just weird. Okay. I can like, I can make myself eat banana pudding, but I don't really want to. Like, I'm just like, I don't really like it.

Andrew Camp: Okay. All right. Fair enough. What's, on the other end of the spectrum, what's one of the best things you've ever eaten?

Christopher Carter: Uh, olive oil from Tuscany. Okay. I'm just straight fresh baked bread. It was the first time I realized what olives are supposed to taste like.

Andrew Camp: Okay.

Christopher Carter: I was like, oh, oh, this is, this is an olive. Yeah. I was like, oh, this is what olive oil tastes like when it's actually fresh pressed. Yeah. It blew my mind. It blew my mind.

Andrew Camp: Was that in Tuscany? Like Yeah. Okay.

Christopher Carter: I was in, I was doing work, um, I was, did some work for the Catholic Church, and I was in Rome, and I was in Assisi, and then I did some other You know, I'm up there. I might as well go visit some farms and stuff like that. Yeah. And so yeah, it [00:59:00] was pretty cool.

Andrew Camp: That's awesome.

Um, and then finally, there's a conversation among chefs about last meals. As in, if you knew you had one last meal to enjoy, what would be on your table? And so for Christopher, if you knew you had one last meal, what would be on your table?

Christopher Carter: Oh, man. Probably,

it's tough. This is a very difficult question. Um, because it has changed over time. I think my instincts I have to cheat. I'm sorry. My instincts are to say, what I would choose ultimately would be beans and rice and cornbread. Because that's like, that's what always sounds good. I can eat that. And it always feels like.

It gives me a sense of connection to myself, but my favorite thing right now that I'd love to cook and make and probably make for dinner is pizza. Uh, I and this is Italy. My wife loves it. We've been twice and like it has infected my soul as [01:00:00] well. Uh, and so, um, I love cooking my own pizza, my own dough, my own ingredients, and it just tastes, it tastes so good.

Um, again, once I was in, people's think, idea about Tuscany, they don't recognize these are farmers. When you go meet them and they just, you see, you actually eat some of that actual rural folks food. Change, it changes everything for you. It changed, it did for me. It changed me.

Andrew Camp: Okay. So what does a pizza look like?

You know, as a vegan, what does pizza, what, what do you put on your pizza?

Christopher Carter: Yeah, it's a, I, I make a vegan, uh, basil pesto. Okay. Um, this is almond. I mean, it's not that hard. It's easy to make pesto. It's vegan. And then, uh, grilled vegetables. So we usually peppers, uh, two different kinds of bell pepper, uh, onion, mushroom, uh, and I have, I do like field roast if I'm going to put some meat on there or what I call meat.

All right. Uh, field roast vegan sausage is. [01:01:00] I, I absolutely love it. Like it's, it's delicious. So I don't eat a ton of vegan meat, but I do put that on it.

Andrew Camp: And do you have a pizza oven at home or?

Christopher Carter: Actually, I have a really good gas, um, oven. Okay. That, uh, is, works perfectly. I use a pizza screen and the key, the key is always getting, you either got to make your own dough or you got to go get fresh dough.

Like that's the key. If you do that, then you're fine.

Andrew Camp: Yep. No, we love pizza night at our house. Um, we use a baking steel. Oh, okay. So, you know, and get that thing smoking hot and we get a pretty decent crust. Yeah.

Christopher Carter: That way. Yeah, so I have a, uh, my oven is a convection and so like it just a fan in there really and with that, with that pizza screen, it allows the crust to get crispy without getting overly burnt.

Um, put it in the middle. I mean, it's. It's amazing. No, it

Andrew Camp: is. Yep. Homemade pizza. You know, I could eat homemade pizza and never feel bad. Whereas if I eat, you know, take out pizza, a couple slices and it's [01:02:00] like, Oh, all right. Yeah, exactly. I regret that.

Christopher Carter: Yeah. And I have a, I think I can imagine, I know, I think you said you have kids, right?

Yep. Yeah. Yeah. So I have a five year old. And so again, pizza is always like, it's easy. He loves it. He loves to help make it. Yep. And so my diet is definitely influenced by my child. I'll say

Andrew Camp: that. Awesome. Well, Christopher, this has been a delight. I really appreciate. Um, your challenge, your invitation, um, but you're also your pastoral heart.

Um, and if people are interested in learning more about you, following your work, where could they find you?

Christopher Carter: Um, you get to my website is, uh, drchristophercarter. com. Um, you can find all my work and research and stuff there. Um, if you want to learn more about the things I do on the more religious, uh, spectrum, uh, I work at, um, the loft.

So that's at the loftla. org. Um, and lastly, I host, um, a progressive Christian podcast that is more about, um, like faith, [01:03:00] uh, politics and pop culture. And so, uh, we've been, um, pretty busy with lots of things happening over there as well. Uh, so that's kind of where I am right now. Um, and, and so you can find me on social media, find me on that stuff and yeah.

Andrew Camp: What was the name of your podcast again?

Christopher Carter: It's called the Progressive Christians Podcast.

Andrew Camp: Okay. Gotcha. Nice.

Christopher Carter: Awesome. Just really, really straightforward. I'm like, this is what it is. Yeah. Perfect.

Andrew Camp: Yep. And we'll make sure to include all those in the show notes. And, um, so again, thanks so much, Christopher, uh, for being a guest on this podcast.

Really appreciate. Um, your time. Um, and if you've enjoyed this episode, please consider subscribing, leaving a review or sharing it with others. Thanks for joining us on this episode of The Biggest Table, where we explore what it means to be transformed by God's love around the table and through food.

Until next time, bye.