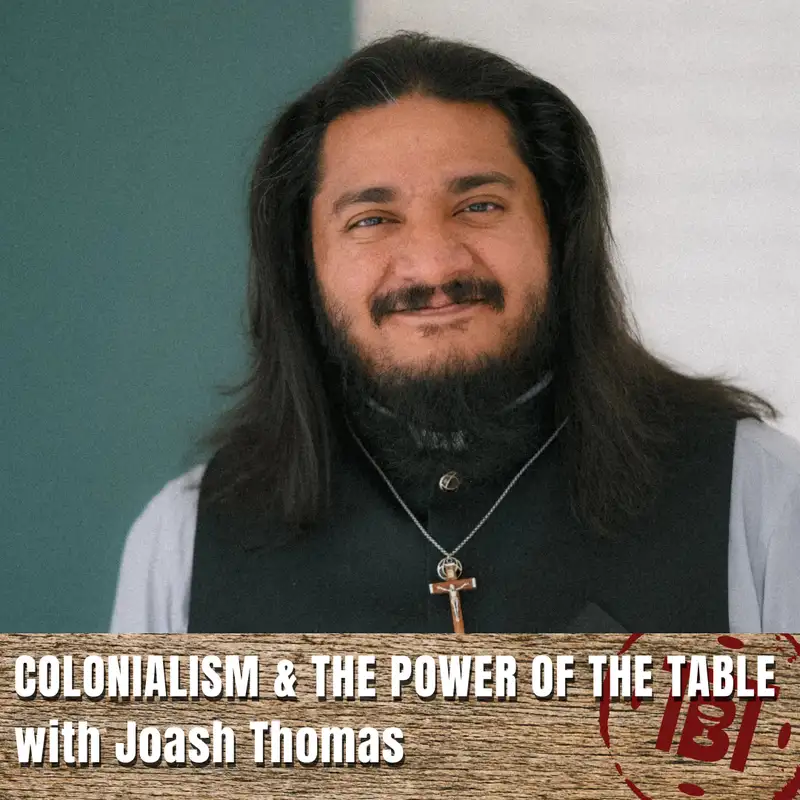

Colonialism & the Power of the Table with Joash Thomas

Episode 52 (Joash Thomas)

===

Andrew Camp: [00:00:00] Hello, and welcome to another episode of The Biggest Table. I am your host, Andrew Camp, and in this podcast we explore the table food, eating and hospitality as an arena for experiencing God's love and our love for one another.

And today I'm joined by Joash Thomas.

Born and raised in India. Joash served as a US political consultant and lobbyist before pivoting to global human rights advocacy. Now based in the Toronto area, he holds a master's degree in political management from the George Washington University and has completed master's degrees in Christian leadership and Christian studies at Dallas Theological Seminary. A deacon in the Diocese of St. Anthony. Joash is also the author of the new book, the Justice of Jesus, which was just released September 30th.

So thanks for joining me today, Joash, it's great to have this conversation.

Joash Thomas: Honored to be here, Andrew. Yeah, looking forward to this.

Andrew Camp: Awesome. Really enjoyed your book. And just as we start, um, I think your background sort of really sheds light into your work and your book and so can you give [00:01:00] the listeners just a little background into your story of who you are and where you were from and your, your pivot?

Joash Thomas: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. So I was born and raised in Mumbai, India. Um. Into a family that's been Christian for 2000 years, going back to the Apostle Thomas, uh, who brought the gospel to my ancestors. And, uh, so my ancestors and my family have been everything from Orthodox to Catholic to Anglican to Pentecostal for the last five generations.

And, uh, you know, I think as a result of that. I tend to be very ecumenical. Mm-hmm. Um, I often feel like a mutt in the larger global church. I can fit in everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Um, and I find myself unable to look down in any one tradition or look up to any one tradition as the perfect tradition.

I think we all have things to learn from each other in the global church. So, um, yep, that was my. Family story [00:02:00] and then, uh, moved to the US when I was 18, uh, worked in the US political world and Georgia Republican politics, uh, before Jesus saved me again, as I like to say. And, and, uh, and then immigrated to Canada after that.

So I'm a two time immigrant, uh, to North America. And, uh, yeah, it's been, it's been a beautiful journey.

Andrew Camp: I can imagine. And so as you were, you know, raised in India for your, a lot of your formative years, like what role does, did food and hospitality play, um, for your family? You know, especially as Christians living, you know, and what we usually think of as a predominantly Hindu, um, area, like how did food and hospitality fit into to who you are?

Joash Thomas: Yeah, great question. Uh, food is such an important part of South Asian culture or any South Asian culture. Um. You know, I think, uh, something that people don't realize about the Indian subcontinent is that, um, there's a plethora [00:03:00] of diversity with, uh, and you would know this as a professional, uh, chef, but like, there's a, a there plethora of options with, uh, cultures and that.

That diversity is reflected in our food. So, uh, India has about 28 states. Um, every state has its own language, um, its own predominant religion, uh, its own, uh, food that's different. And so, and everyone has their own different way of making, uh, ani or a chai. Mm-hmm. Uh, and so. There's beauty when all of that comes together in a city like Mumbai, which tends to be very cosmopolitan, uh, because it's an urban center, it's a city of Bollywood and all that.

Uh, so people come from all over. My grandparents came from the south. Um, and um, and it's beautiful. You get to live in multiculturalism. Mm-hmm. And you get to enjoy the best of all the worlds of food. Yeah.

Andrew Camp: Yeah. Awesome. If you [00:04:00] were to have a comfort food dish from India, like what's, what's that dish you go to that just is like, screams home to you?

Joash Thomas: Great question. Uh, it would be a biryani. Uh, I can have biryani with meat for breakfast, lunch, or dinner.

Andrew Camp: Gotcha. And for listeners who aren't familiar with biryani, like what can you describe it? Give us, you know, yeah. Aromas, flavors, you know, like, make us hungry a little as we

Joash Thomas: Absolutely. So the good news is.

Almost any Indian restaurant should have this dish. Right. Um, usually a chicken biryani, or I prefer a lamb or a goat biryani, if you can find it. Yep. Um, and biryani was brought to us, uh, from the moguls, um, who were our rulers for many centuries. And, um, they came from Persia. So it's a good blend of Persian, of Ghhi.

Uh, Pakistani Indian cuisine. Uh, it's basically, um, rice, uh, with meat. Um, some parts of India throw in potatoes, others throw in [00:05:00] tomatoes. Uh, you can make it your own, depending on India probably has over a hundred different types of biryani. Um, and then something else I'd say is. Uh, the, the main star though is not the rice.

The main star of the biryani is the meat. Um, so you cook the rice and the meat separately, and then you cook it both together. Uh, and you ultimately want the rice to be flavored by the meat. Hmm. It's beautiful.

Andrew Camp: Yeah. And do sometimes some bits have a. Pastry crust over the top, correct? Yes.

Joash Thomas: Yes. Fried onions.

Okay. Okay. Yeah, yeah. Oh, or pastry. Yes. I get what you're saying with, with non, uh, kind of covering the top. Mm-hmm. Yes, a hundred percent. Yeah. Okay. Um, uh, unfortunately not an option if you're gluten-free, but No. Uh, but otherwise, uh, terrific option. I love it that way.

Andrew Camp: Yeah, no, there's an Indian restaurant near my parents in Orange County that we've had biryani from, and they have the pastry crust and they come to the table and shatter it for you.

Um, that's awesome. Phenomenal. That's that's a

Joash Thomas: very [00:06:00] luxurious way to eat it for sure. I love it. Yeah. Yeah.

Andrew Camp: No, this was, this is, yeah. This is a higher end fun. Mm-hmm. You, they're, um, halal, um, you know, makes sense. But yeah, they're just, yeah. It's good. Indian food is just so delicious and flavorful. And the com, the amalgamation of spices and heat and texture.

Yeah. My wife and I love it.

Joash Thomas: Uh, yeah. It sounds like you're very familiar with it. Uh, I love it. Love it.

Andrew Camp: I love Asian food. You know, I think Asian food, just, I think I, I love Chinese food, Thai food, Korean, you know, Indian food. I think that just the Asian continent just makes food in such a beautiful way that yes, I'm partial to.

Joash Thomas: A hundred percent. Yeah. Yeah. And again, there's so much diversity. Yeah. And it all mixes. And so for example, you probably know this Andrew, but there's this whole genre of food, uh, called haka food or Indian Chinese food. Okay. Um, which is not real Chinese food. It's like. [00:07:00] A, a blend of, uh, Indian food and Chinese food.

So it's Chinese food, like fried rice and lo man and all that. But with, with spices, with Indian spices. And, uh, it's quite popular across India, especially the north. But, uh, brought to us by the haka people, uh, who, um, look, look Chinese, but are culturally very Indian and, uh, live in India, uh, for generations.

Andrew Camp: No, I've not heard of hook of cuisine. And that does sound, yeah. Okay. Yeah, we, we could probably talk about food most of this time and then get really hungry, but, um, you know, so you come to America, you're working as a political consultant Yeah. And, and the Republican party. And you say that Jesus saved you again.

And so like what, what was that process and how did that transition go and like when did you sort of begin to realize, hey, I need to get out of political. The politics or this sort of politics for my own sake.

Joash Thomas: Yeah. Yeah. Uh, I got into politics because of [00:08:00] my Christian faith. I think that is the reality I think many Christians do.

Andrew Camp: Yeah.

Joash Thomas: Um, for me in specific, it was because of my passion for justice. Uh, I've always been passionate about justice as a global south Christian, and then came to the west and realized that, um, people in the church don't really talk about justice and seen as. Marxist or woke or out there and, uh, ended up just, uh, yeah.

You know, that was, that was a very early observation I had, and I mentioned that at the beginning of the book. Um, but then. You know, I, I wanted to make a difference for my marginalized neighbors. I thought politics was the best route to do that. Um, so I got involved with a few local politicians who happened to be with the Republican Party.

And as I worked with them, uh, my theology, my, uh, faith started to be shaped by what I was being mentored in from them. Um. [00:09:00] And, you know, I, I was never, um, so, you know, there were lines I wouldn't cross like I left ultimately with the rise of Trumpism. 'cause I felt like that was a line I never wanted to cross.

Um, and, uh, you know, I was, I I never crossed, um, a bunch of different lines, um, that I felt like were. Opposing to our marginalized neighbors. But, um, but you know, I think in the American South Evangelical Church, you're conditioned into thinking that this is the only option for Christians, uh, this history behind this racial history behind it too.

But, um, you know, so, so I had to. Um, I, I had to have a, a series of rude awakenings, uh, that I talk about in the book, and then ultimately it's because of my passion for justice for all my marginalized neighbors that I had to leave this political party that only embodied justice for. A few categories of marginalized neighbors while neglecting everyone else.

Um, not that the other party is any better, um, um, and they're, you [00:10:00] know, slightly better, uh, but, uh, you know, not, not necessarily championing justice for all our marginalized neighbors. So I think over time I've come to realize that. The voice of the church, uh, should be an independent one that speaks truth to power, regardless of who is in power on behalf of our marginalized neighbors at all times.

Yeah,

Andrew Camp: That's what I really appreciated about your book is you know, that, you know, you're, you, you balance this fine line of, you know, like speaking truth, you know, and harsh truth, you know, and good truth, but also wanting to maintain hope for even the white evangelical church. Like you're not Yeah.

Like, and which I really appreciate. 'cause sometimes it's so easy as all of us are trying to make sense of our upbringing as evangelicals. Like, uh, you know, where do we fit? You know, and wanting to throw the baby out with the bathwater. But you seem to be like, no, the church is still the hope and we can be a voice.

And so like, how, how do you do it? Like, 'cause it's, it's, it's tricky. [00:11:00] It's not an easy line, right? It's easier to live on the extremes, but you seem to be walking this good fine line that wants to give hope to both sides.

Joash Thomas: Hmm. Yeah. I think for me, so much of that was shaped by my time on the margins. Uh, because when I started working in international human rights after leaving Republican politics, um, I did not expect to find Jesus on the margins as much as I did.

Um, so I say in the book that, yeah. I tr I thought I'd find Jesus in the halls of power of Georgia Republican politics, didn't find him there, found him on the margins. When I started working among survivors of trafficking and violence, uh, they taught me way more about Jesus than, uh, I could have ever imagined, even if they never mentioned Jesus by name.

Because you know, you, you need to cultivate the eyes to see Jesus there. And the reason why I mentioned that is because once you learn to see Jesus. In the most unlikely places like the margins.

Andrew Camp: Yeah.

Joash Thomas: You then [00:12:00] start to have eyes to see Jesus again in other unlikely places like the white Evangelical Church or a Muslim mosque or Hindu temple.

Or a Sikh temple, right? Like, 'cause Jesus is everywhere. Christ is all an in all. And he's transcendent everywhere. And so if I think that I can, if I believe that I can find Jesus in the margins, if I, if I believe that I can find Jesus. Um. In, uh, other cultures and religions, uh, find signs of him there. Then I think we can also say the same for the white Evangelical church because God has not done, he, he hasn't given up on his children anywhere.

Andrew Camp: I appreciate that of, you know, and you reiterate that in the book of that, you know, so often. Those of us in power, or those of us who have benefited most from colonialism, and we think we we're taking Jesus to the margins, but you really wanna help us see that? No. Like Jesus is already there.

Like how do you cultivate the eyes to see Jesus in the margins? Um, which is such a [00:13:00] beautiful, more profound but yet harder task.

Joash Thomas: Yes, yes. It definitely comes with its challenges. And, and you know, like I. It also comes with a level of privilege too, right? So there are many people from marginalized communities who have been harmed by the white Evangelical church, and they may not have the capacity or the, the healing from the trauma or the privilege to go into these spaces and be messengers for peace and justice.

But others could, others maybe from majority white. Evangelical cultures, um, uh, and especially men, you know, do have that privilege of being seen as the same or accepted as the same. And, and they, they can be peacemakers in these contexts that marginalized communities, uh, like mine, uh, as a brown immigrant possibly can't.

And so I think it's for all of us to discern. Where we can step in with the privileges that we have, [00:14:00] just like Jesus steps in for us with Right. Laying aside his divine privileges in, uh, Philippines, chapter two, and, uh, taking the form of marginalized human flesh.

Andrew Camp: And so as we begin to want to step into these places, you know, obviously a lot of talk has been centered in the recent years with the rise of Trump, of this deconstruction.

But you go further to say deconstruction without decolonization is pointless and ultimately does nothing for our marginalized neighbors. Yeah. Um, so help us, help our listeners. Help me, like can you unpack that statement because you know, you're asking us to take another step of what it means to embody Jesus in these turbulent times.

Joash Thomas: Yeah, absolutely. And I say this throughout the book too. You know, colonialism wasn't just bad for the global South church or for the global south. Uh, it was also bad for the Western church that participated in it. Right. And I've learned this working in the international human rights, the [00:15:00] justice space for the last decade.

Injustice isn't just bad for the humanity of the oppressed, it's also bad for the humanity of the oppressors.

Andrew Camp: Yeah.

Joash Thomas: Uh, and those on their side. Mm-hmm. And in the case of Western colonialism, the Western Church. Participated in colonialism benefited from colonialism. Uh, and whether we realize it or not, it shaped us.

It shaped our theology, it shaped our praxis, it shaped the way we see Jesus, the way we love God and love neighbor. Um, yeah. And so I think, I think it's important for us to reckon with that because something I see is I often see a lot of well-meaning, uh, progressive ex evangelicals leave the Evangelical church and then embody the same type of colonized fundamentalism that we see, uh, them being harmed by, right.

Because that's all they've ever known. And so this is where I challenge us in the Western Church to learn from the church and the margins to learn from the global South Church. Uh. Uh, feminist [00:16:00] theologians, L-G-B-T-Q, theologians, you don't have to agree with everything they say, but, but hear 'em out and be challenged because again, Jesus is everywhere,

Andrew Camp: right?

And that's the challenge of, okay, how do we begin, you know, if this is the only air we breathe, or you know, the water we swam in whatever metaphor you want to use, right? Like right to begin to see how it has impacted us. And it's hard because again, when, when you're in it, you know, it's hard to, for me as a white, middle class, evangelical, my whole, you know, born and raised right. Like, you know, to see it. And so like where, where do you see the, um, the gospel has been co-opted by colonialism. Like, can you give us an example just so like, you know. Yeah, maybe start to take the scales off of our eyes.

Joash Thomas: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I'll start with this.

Um, and I mentioned this in the book as a key question that, you know, pushed me to decolonize my own theology as working in international human rights in the anti-human trafficking space [00:17:00] for the past decade, and then regularly coming across evangelical pastors, both in the US and Canada, who would say things like.

What's the point of rescuing children from trafficking if their souls go to hell, aren't they dead in the water anyway? Right. Um, or sitting across a friend from, uh, the, the staff team of one of the largest churches in Canada, um, who oversaw, you know, missions outreach and him just. Telling me that, um, you know, his, his pastor says that the gospel is both physical and spiritual.

Um, his pastor says that justice is important, uh, but when it comes time to budgetary decision makings within the church, you know, um, when the choice is between, uh, rescuing bodies from human trafficking or violence. Or airdropping and I, this is a real example. Airdropping parachuting radios with Christian programming into parts of Europe.

They'll go with that because, you [00:18:00] know, um, if, if we can save some souls, uh, that's worth it, then, then rescuing bodies and them not finding Jesus. Right. So it, it kind of raises these questions of, okay, like where does this come from? And I think in the book I. I spell out a few tenets of the colonizer theology.

Andrew Camp: Yeah.

Joash Thomas: Um, and, uh, yeah, happy to talk about any of that. But one of the things that I spell out is, you know, uh, just this belief that. Jesus came to rescue souls more than bodies, right? Uh, Jesus cares way more about, uh, the future of my soul, the salvation of my soul than the freedom and wellbeing of my human body.

When a. If you read the gospels, that's just not true. Uh, Jesus cares both about the body and the soul. He's healing sick people. He's, uh, setting people oppressed by demons free. He's, um, uh, you know, he's feeding hungry people like he cares both about the body [00:19:00] and the soul. But, uh, you see this dichotomy in the Western Church because of colonialism, because colonizers and slave holders, uh, told people they colonize and enslaved.

Jesus cares way more about your soul than your body. So don't worry about the chains on your bodies. Uh, just focus on the spiritual and, uh, and the same thing is said today in the church, and it hurts us way more than we ever know, and it it shapes us to resist justice today.

Andrew Camp: For sure. No, and it sort of goes back to Jesus' words in Luke four or you know, Isaiah 61, that prophecy too, of which Jesus reads from in Luke four of like, do we actually think those are literal words or is it just a spiritual that Jesus came to set the oppress free, or we mean the spiritually oppressed or Jesus came to loose the chains?

Like, no, your spiritual chains. Right. Uh, I remember interviewing with a church, this was back in 20 20, 20 21, and we were talking and I mentioned, I think, you know, I. When Jesus is saying that like I think he means something physical and like actual, literal, and [00:20:00] the pastor was like, well, you're gonna have to prove that to me 'cause that's just not the case.

And you're like, alright, I think this interview's done. Like I think we're diametric. But you know, it's that where we see Jesus's words and we take them spiritually instead of literally.

Joash Thomas: Yes. Yes. And I would say that that's horrible biblical exegesis. Uh, you know, like I went to Dallas Theological Seminary, the most conservative evangelical theological seminaries, and even in the most conservative evangelical seminaries, you're taught to take scripture seriously by looking at the original context.

So let's look at the original context of Luke chapter four. Right,

Andrew Camp: right.

Joash Thomas: Who is Jesus's audience when he's saying this to? Um. They're poor people, people who are physically poor and physically oppressed by the Roman Empire. Right? And, and, uh, so, you know, we see verses like, uh, Jesus saying blessed of the poor.

And, uh, you know, we, we say, [00:21:00] oh, well, you know, Jesus just means spiritually poor. Yeah. Uh, when Matthew's gospel says, no, blessed of the poor. Um, and, and it's. He's actually talking to poor people who are under the boot of empire. Right. And so, um, I think it's so hard for so many of us in the Western church to step aside from our privileges, our 21st century modern lenses to see okay, Jesus' audience, who he was preaching this to, how would they have received this as good news?

And, and when we do that, and I think we can do that today by learning from our marginalized neighbors, um, who are under the boot of Empire. And, uh, it's when we do that, that. The gospel just hits different.

Andrew Camp: Mm-hmm. Right. 'cause you've mentioned that empires are never set up with their marginalized neighbors flourishing in mind.

Joash Thomas: Yes.

Andrew Camp: You know? Yes,

Joash Thomas: yes. They're, they're only set up to serve the rich and the powerful, uh, and the people who serve the rich and the powerful, and, uh. And that is not the job of the church. The job of the church is [00:22:00] to stand in the gap. Uh, you know, we come from a long line of prophets who stood in the gap between the poor and the oppressed, and those with power, the rulers and who spoke truth to power on behalf of the poor and the oppressed, sometimes at great personal cost.

And who did that in love, uh, who did that from a posture of, of truth, but also from a posture of love for both the oppressed and the oppressor. And that is the task of the church today.

Andrew Camp: And your book really wants to bring, okay, how do we actually move into these spaces? How do we bring justice to bear?

Um, and one of the places obviously that I wholeheartedly agree with you and shouted Amen posted about it on Instagram is recentering the table. Like, and this is, you sort of even begin here, you say, like, really to decolonize our, our gospel, we need to decenter the pulpit and recenter the table. And you, um, specifically the, the Lord's table?

Yeah. Or the Eucharist or, um, however your tradition calls it. So [00:23:00] like why, why, why do we need to start there? Uh, yes. Yes. 'cause the Western Church would say, we just need more education. Like, yes. You know, if we just preach better, if we just preach the gospel, like Right. You know that that's gonna change, that's gonna change.

Joash Thomas: Yeah. Yeah. And, and that is absolutely a myth because how's that working out for us? Right. And, and don't ask ourselves as church leaders. I say this as an ordained church minister myself, but ask our marginalized neighbors, do they feel included in the church? Right? Do they feel safe and protected and advocated for in the church?

And the vast majority of them don't in the Western church. Right? And so it's not working out well for us. Um, so what I would say to that, uh, lovely question is. You know, just look at church history, right? Take a survey of church history and again, I learned this in Evangelical Theological Seminary in the west.

Yeah. Uh, for the first 1500 years of the church. It wasn't the pulpit that was the center of the Sunday morning worship. It [00:24:00] wasn't the preacher in the pulpit. No, it was the table. Yeah. And the theology of the eucharistic table for the first 1500 years of the church, um, was that Jesus was physically present at the table somehow in a mysterious way.

We can't explain it, don't know how this works, you know, that's where faith comes in. But Jesus is present at the table, and so Jesus is the center of. Uh, our attention, um, and, and, and our liturgy and our preaching, all of it points to pulling people to the table and to be reconciled at the table. And then from the table we go out to bring peace and shalom and justice into the world.

Right? And that was always the way the liturgical services was set up. Um. And, uh, not, not to say that that didn't get co-opted by Empire two, but you know, what's easy for the empires of our day today is to co-opt the pulpit. Um, you know, post Reformation, the pulpit became, uh, the center of the Sunday morning [00:25:00] worship, and the preacher and the pulpit became the center and, um.

You know, when the preacher has a scandal or the, or the preacher disappoints without a scandal, people lose their faith because their faith isn't centered on the real presence of Jesus at the table. It's now been replaced by this preacher, um, who, you know, is, is a fallible human being at the end of the day.

Right? Yeah. And so, so I say, and I think you quoted this, but you know, let's decenter the, the fallible presence of the preacher at the table and, and recenter, um, the infallible presence of Christ at the table.

Andrew Camp: Right. But that also makes, you know, we need a richer theology. 'cause I've, you know, part of it has been, we have an emaciated theology of the table.

Like, you know, the tradition I grew up in, you know. We would celebrate communion maybe once a month, and it would sometimes be in the evening and not part of Sunday morning. Um, you [00:26:00] know, and even with churches I've been to that celebrate with it weekly, it's sort of an add-on. Like there's very, there's very little theological, it feels like reflection, you know, and again, I'm not saying, you know, we need more education, but like we do need a richer, it seems like we need a richer theology of the table.

Yes. Um, and so how, where. You know, many of us, many of my listeners probably don't have power to change the rituals of a church. But how do we begin to then think about the table in a more robust way? Because too often it's a Jesus and me moment, a forgiveness of sins. Mm-hmm. You know, where I just encounter Jesus individually as a sole person versus a robust communal activity where we realize how much we actually have in common.

Joash Thomas: Absolutely. Absolutely. And I think this also comes from western individualism. Yeah. Um, of, you know. Just reducing our faith [00:27:00] to an individualistic expression when that wasn't the case for the early church. Right? So no Acts chapter two, you see the early church gathering regularly at the table and then going from that table to proclaim the goodness of God into the brokenness of this world, right?

The good news of Jesus holistically and word. And indeed and, uh, these, these tables were like the center of, um. That revival in their communities and in their society. Um, the, the magic happened at the table, and I think what's really powerful about the table is that it levels everything out, right? Mm-hmm.

Socioeconomic status, caste status, all of that is leveled out at the table. Uh, racial status, all that's leveled out because at the table, everyone's the same, everyone's one before Christ. Uh, there's no Jew nor Greek. Uh, no, you know, no [00:28:00] slave nor free, no male, female. Yeah. Uh, pro-Israel, pro-Palestine, um, you know, uh, pro women's rights, uh, anti-abortion, like there, there's none of that.

None of those manmade distinctions exist at the table. Um, all we have at the table are us as one humanity, uh, and, and God through Christ mediated through Christ. And, and, uh, we're reminded that, um, we have more in common with each other, uh, than our differences. And, and ultimately, um, Christ reconciles this at the table.

So yeah, in the early church you see. The table being this, um, this important thing. Mm-hmm. Um, so much so that in first Corinthians, you have Paul teaching the church. Hey, let the poor come and eat first at the table. Yeah. People who haven't eaten, people who are hungry, let them let them go first. Eat at the table, uh, and then everyone else.

Come and, and, [00:29:00] uh, and even that was, oh my goodness, preferential treatment for people who are poor, right? That is not the way first century society was set up. Uh, that is not the way 21st century society is set up either, but, um, but there's something beautiful about recentering the table and recentering Jesus's presence at the table.

So, uh, you know, I see a lot of progressive evangelical churches centering the table, but they do so in a way. Uh, that doesn't acknowledge Jesus's real presence at the table. Uh, they do so in a way where it's like, well, if you just have a bunch of, uh, food and, you know, uh, chips and crackers and, and grape juice, like, that's fine.

Like, you know, uh, that's, that's all you need. But I would, I would say no. I, when, when we say that we're being cut off from the tradition of the church, which for 1500 years acknowledged that there's something. Happening Right. Uh, through the elements being served at the table. Yeah. Uh, by leaders in the church who, you know, when they hand out the [00:30:00] body and blood of Christ, uh, it's not about them.

They're taking a step back and they're saying The body of Christ for you. Mm-hmm. Yeah. The blood of Christ shed for you and for your healing and through your healing, the healing of the world.

Andrew Camp: And that's the beauty of the table. And yet in, you know, like you said in one Corinthians 11, Paul Admonishes, the church, 'cause Empire has already moved in, within, you know, less than a decade probably of a church starting the Empire.

Yeah. And Empire mindsets quickly to. Co-op and people are pro, you know, we're prone as humans to move back to what we know and is comfortable. And that's yes. You know, so like, even then, like as we wanna recenter the table, we empire and politics and old ways of being can quickly creep in, which is really challenging 'cause like, it's not easy, right?

Like our pull is always back, it feels like towards, you know, separatism or, um. You know, empire minded thinking [00:31:00] versus, you know, how do we keep Jesus as the focus?

Joash Thomas: Absolutely. Absolutely. Uh, individually and as a church and as a collective society, and this is why I think, you know, you have, uh, I'm not talking about what, what has been called a revival in the North American church because, you know, there are people still being enslaved and all that.

How much of a revival was that really of a holistic gospel demonstration. But, but you know, I think throughout. Church history, you have revivals seen and unseen that emerge and pop up and people find their way back. Mm-hmm. To Jesus. But then the allure of empire is too strong. And we haven't done a good job of discipling our people to resist empire, uh, resist empires of our day to watch out for that.

We have over individualized scriptures like. Don't be tainted by the world. And we make [00:32:00] that all about sexual sin when in reality that's actually about protecting ourselves from the tainting of the systems and structures of the world, like the oppress oppressive empires of our day and the way that conditions us to come up with our own caste systems wherever we are.

So, absolutely.

Andrew Camp: And so as we decenter the table sort of in our collective. Um, worship gatherings, faith communities, churches, you know, whatever that is for, you know, people like how then can then the table in our own homes or in our neighborhoods, then be areas of decolonization and, um, you know, flourishing for, for everybody.

Joash Thomas: That's beautiful. Yeah. Yeah. I think it starts with. Uh, preferential treatment towards people who are poor and oppressed. Right. And this is something that I found in Catholic social teaching and liberation theology that I feel like the Evangelical Church desperately needs. Like if there's [00:33:00] one thing that people walk away with after reading my book, I hope it's this thing, uh, it's that God always stands with people who are poor and oppressed always.

And if God does that, then we as the church. Have a responsibility to do the same regardless of who's in power, regardless of whether or not we've been conditioned to hate the people group who are being oppressed, like our Palestinian neighbors right now. Mm-hmm. Uh, if we're conditioned to distrust them because they're from a different religion, um, like Islam or, um, a different ethnic group like the Arab Group, um, you know, regardless of all that.

Uh, we're, we're called to stand with those who are being oppressed, even if the oppressed and the oppressors switch sides, because when the oppress and the oppressors switch sides, which happens regularly throughout human history, then God also switches sides to stand with the newly oppressed people because that's where Jesus is.

And, uh. Now, does this mean [00:34:00] that God hates the rich and the powerful? Absolutely not. Um, but the rich and powerful are gonna be fine because they have wealth, they have resources, they have the supportive empire. People who are poor and oppressed have no one to stand on their side. And so God stands on their side not because of their ontological goodness, but because of the goodness of God.

Uh, because that's who he is. He stands with the powerless. And, and so I think. We need to bring that to the table.

Andrew Camp: Yeah,

Joash Thomas: we need to take a look around that, around that table and see who are we including here and who are we keeping out of the table? And. And, and, and I mean, think about it this way, right?

Like if Judas had a seat at Jesus's table and Jesus knew yeah, who Judas was, what he'd done, what he was about to do, betray him. But if Judas had a seat at Jesus's table, then all of us have a seat at Jesus's table. What we do after we walk away from the table is our choice, because God gives his [00:35:00] agency, but um, the table is a space for everyone, uh, who wants to encounter Jesus.

I say this to church leaders too, who, you know, um, wouldn't be comfortable with having people who are not Christian participate at the table. You know, I would say to them, well, if we believe that Jesus is at the table, or we believe that there's something holy about this, that points to Jesus, right?

Whatever our theology is, we believe that this points to Jesus even in some way. Why would we keep people from experiencing Jesus? Especially if they wanna, you know, amen and

Andrew Camp: amen.

Joash Thomas: Let him come. It's a feast. And uh, you know, I wish Jesus preached a parable about, uh, there being a lot of empty seats at the table.

And, uh, wait, actually he did, right? He did,

Andrew Camp: yeah. And Judas had a seat at that last table. Jesus washed his feet. Jesus offered him. The first commun, you know, he, you know, like [00:36:00] he offered Judas. Yes, yes. Forgiveness. Like, I, you know, there's something that happened there that I, I, I wanna believe Jesus in love is still reaching out to Judas, right?

And so, you know, like, yeah, like, so if Judas is there and Jesus serves Judas, who are we to deny other people that opportunity to experience Jesus?

Joash Thomas: Absolutely. Absolutely. And this is why as much as I, you know, have been shaped by the beautiful theology of even the Catholic church, I disagree at times when that theology of the table is weaponized.

When you know when. Uh. Uh, certain politicians are a banned from the table by the church because of their political views one way or the other. No. Wouldn't you want this person to experience Jesus and be transformed by the touch of Jesus and the presence of Jesus? Right? And, and so I think, uh, our, our way of understanding God and neighbor has to shift to a more love oriented, more generous [00:37:00] version of God.

And if we're okay with accepting the grace of Christ for ourselves. Despite our past and what we've done, then, then why would we not do the same for our enemies?

Andrew Camp: For sure. I always thought, like, I remember reflecting back in 2016 at, you know, the election, first election of, um, president Trump that like, if, if he walked in to a church, would I offer him communion?

Like, and if my heart says no, like there I need to Yeah. Do something, you know, internally. Yeah. You know, and that's one example, right? Like that's, you know, my example, but like how, who, you know, how, how do we move towards people we, we despise, whether they're, you know, people in power or people on the margins.

Totally. Totally. 'cause like you said, you know, like it, you know, Jesus isn't on the side of the oppress so that the oppress can become the oppressors. Yes. Anybody's flourishing should result in the flourishing of everybody. [00:38:00] Yes. You know, there's all of this going on, and so it's this tricky balance of, as we think about, what does it mean to bring justice to bear?

Like how it's for all, it's for the flourishing of all.

Joash Thomas: Absolutely. And Andrew, to your point of what happens when the President of the United States, regardless of who it is, yeah. Or your local congressman, a member of Parliament, a Prime Minister, walks into your church. Well, what tends to happen these days is.

We give him the pulpit.

Andrew Camp: Yeah.

Joash Thomas: And again, that's because the pulpit is the center of the worship, not the table. Now if the table were to be the center of the Sunday morning worship, um, and the politician walks in. We'd say, welcome, come and receive at the table, right? Yeah. But yep. But this is Jesus's table.

This isn't the pastor's table. It's not the pastor's pulpit. This is about Jesus this Sunday morning. So yeah, come receive like everyone else, be one. You know, grace is for you two. Yeah. And uh, and, [00:39:00] and, but, but unfortunately we've gone the way of. Centering the pulpit. So we give the pulpit away as a way to honor these political leaders with the best intentions.

And then the pulpits get colonized by empire. Right. And their political agendas. Yeah.

Andrew Camp: Mm-hmm. And so we list end up listening to, to the people in power telling us what we think we need and what we think we need to do. Versus your whole point is we need dialogical partnerships with the people on the margins.

Yes. You know, we need to sit at their feet. Um, those are the people we need to be sitting at, you know, learning from versus those in power.

Joash Thomas: Absolutely. That, that is such a beautiful connection, Andrew, because I think the point you're making is if we, if we make the pulpit the centerpiece of the Sunday morning and we invite people with power, uh, we center their voices, then we're actually actively discipling the church against what it was always meant to be, which was okay.

A space for the powerless, um, to behold [00:40:00] God as their liberator and rescuer.

Andrew Camp: Mm-hmm. And so, uh, I think many of my listeners, and this is where I struggle with, we, we realize the problem, we see the issues, we see the pain, the brokenness, and you know, there's many instances where for the church to stand in the gap today to speak for the oppressed.

Like so where, how do people start moving from sort of a criticism mode to an act, you know, an active. Prophetic mode to, to bring justice to, you know, Jesus, to bear, um, sort of on these issues. We, we see all around us today.

Joash Thomas: Yeah, that is a great question. And, you know, uh, when my publisher came to me to ask me to, uh, rework my proposal for the book, originally it was gonna be a book that leaned more on the diagnosis side of Here's what's broken.

Andrew Camp: Yep.

Joash Thomas: Uh, with a little bit of prognosis, but Brazos said, Hey, would you actually. Do it the other way and make it more hopeful. Prognostic. [00:41:00] Here's where we go from, uh, from this point, kind of a book versus, uh, just diagnostic. Because a lot of good diagnostic work has been done by historians and smarter people over the last many years.

Yeah. Uh, but where do we go from here? Uh, what is the, how do we, yeah. Where's the voice of the practitioner and how do we embody the justice of Jesus? And so most of the book, like. You know, really six out of nine chapters in the book. The first three chapters, a diagnosis. And then, uh, the next six are hopeful prognosis, where we go from here.

And the last three chapters in specific to get to your question, give us very prac, very practical ways, right? How we actually embody the justice of Jesus. And so I give three ways to do that. There are each chapter titles too. Um, uh, pray. Partner and advocate, right? Mm-hmm. I think these are the three most effective things.

An individual Christian or. Uh, a church community can do together, pray, partner, advocate. Uh, so on the prayer side, um, I, [00:42:00] I try to help reframe prayer for us because so many of us have been conditioned to see prayer as this individualistic vending machine thing. Mm-hmm. Uh, that's just intercessory versus something that actually shapes us to be like Jesus and the world that we live in today.

Yeah. Uh, like the Lord's Prayer does, you know? Yeah. The prayer that Jesus taught us to pray. And so, um, so. So I would say start with prayer. Um, but don't just stay there because if your prayers aren't shaping you to become more like Jesus, then you're praying wrong. If your prayers aren't shaping you to take action for justice on behalf of your marginalized neighbors like Jesus did, then you're doing prayer wrong.

Uh, so prayer is a starting point to be connected to the spirit and to have the eyes to see what the spirit's doing around us. Um, and then look for ways to partner with the spirit. Because the good news is that. The church and the margins is already active in partnering with God, Christians and the margins are already doing this.

Uh, so look for people of peace like that. Yeah. Uh, within the [00:43:00] church and outside the church that you can partner with to bring wholeness in. Shalom. Um, and, and that also means financially in sacrificial ways, uh, for the wholeness of the world. And then, uh, I talk about advocacy as well. And uh, this was probably one of my favorite chapters to write because, um, I have about a.

Decade of advocacy experience in three different countries in the international human rights space. And I just share tips of what I've seen everyday Christians do to build relationships with government leaders and power, and to move that power on behalf of our marginalized neighbors.

Andrew Camp: Yeah. And you know, you're, those last three chapters were great.

And it's hard because, you know, like, what, where I need to partner and advocate for will be different than you probably, you know, and just, not even just because of location, but because of passions and, um, you know, what, how God has created me to act in the world. Totally. Um, you know, and so that's, you know, the struggle is like, okay, we can, [00:44:00] there's no one size fits all.

Yes. Uh, you know, yes.

Joash Thomas: I and I, I tell people this throughout the book too. I can't tell you what this looks like for you. Yeah. These are just a few ideas. Yeah. It's, it's between you and the Holy Spirit to discern how the spirit's leading you between you and God and uh, and then. Don't do it alone. Find others running the same direction and go in community with them.

And this is what the church was always meant to be. Uh, but we've made it about a Sunday morning sermon experience that does nothing for our marginalized neighbors.

Andrew Camp: No. Um, I was just recently, um, one of our big, our family food center here in Flagstaff held an anti-hunger summit, um, last week, you know, where they brought in people from all over Northern Arizona to, you know, network and, you know, think through, okay, how do we fight hunger and end hunger and.

I think it was a great summit and there was lots of learning and like, you know, speakers on [00:45:00] from public health organizations in Arizona talking about the impacts of HR one on SNAP benefits and that like, they're like, worst case scenario is SNAP benefits in Arizona go away because you know of the wrong politicians being elected in his words.

Like

Joash Thomas: right.

Andrew Camp: But like, but the sad thing was like there were very, it felt like there were very few faith communities present, you know? Um. Wow. And so, you know, here's an opportunity it felt like of to come together and work across divides, you know, and across communal, you know, like a coalition forming, you know, and like, okay, where where can the faith community step in to help and work together and raise awareness, um, on these aspects?

Joash Thomas: That's, and that's beautiful that there are people outside the church doing this.

Andrew Camp: Yeah.

Joash Thomas: And at the same time, it's a shame that people at the church, people from the church, uh, and the church isn't represented in conversations like this, because then clearly there's a disconnect between our [00:46:00] prayer and our action.

Right. So,

Andrew Camp: right.

Joash Thomas: Clearly, if we're praying, give us to stay our daily bread. And I mean, I did a Instagram video about this recently. If we, if we pray, give us this day our daily bread, then we will protect snap benefits from being cut, um, to American children where one in four American children, if the statistics I'm familiar with are correct, uh, one in four American children receive snap benefits.

So how can we pray? Give us this day our daily bread and then vote for politicians who, um, cut, literally cut out bread from marginalized communities and children.

Andrew Camp: And that's where the, you know, the struggle is of, you know, I think many of us are struggling. There's so much bad news. It feels like, um, that yeah, we're, you know, we're overwhelmed and, you know, I think my tendency is I shut down, um, you know, or I become so overwhelmed I, you know, you freeze.

Um, and so like how to take those small steps, um, [00:47:00] you know, and, and continuing persevering, yeah. Um, is, is the struggle.

Joash Thomas: Absolutely. Absolutely. And, and this is where prayer comes in, right? Yeah. Because, uh, what you talked about freezing. Um, or, or flight. Or fight, yeah. These are trauma responses, right? And, and trauma therapy therapists will often tell you that, um.

You know, even in the scientific community, there's this consensus of a higher power, you know? Yeah, right. And, and leaning on the higher power to guide us. And for us as Christians, uh, we have more of a framework around what that higher power looks like. Um, but it's, it's, uh, it's sad that, uh, the world is the way it is and, uh, yeah.

My hope is that people. Are able to see prayer as a way of leaning on that higher power, um, on behalf of our marginalized neighbors, because again, [00:48:00] guess who cares more about the brokenness in the world than we do. God does. God does, and God is looking for people across the land to, to just. Just rise up and have the eyes to partner with him.

Andrew Camp: Mm-hmm.

Joash Thomas: Whatever little ways they can.

Andrew Camp: Yeah.

Joash Thomas: Um, 'cause ultimately, and I say this in the book too, um, our western capitalism has shaped us to prioritize success. Mm-hmm. But God doesn't call us to success. He calls us to faithfulness. Yeah. And so what does it look like for us to be faithful in our context today?

Andrew Camp: Mm-hmm. You know, and I, yeah. I, I just keep coming back to this idea of what does it mean to then. Learn from our marginalized neighbors, like, you know, yes. The, the colonial gospel will say, Hey, we go in with all the answers. We're here to fix you. Whereas you're, you're asking us in humility to learn and to say, okay, let's just listen.

You know, um, versus prescribing their, their needs. [00:49:00]

Joash Thomas: Absolutely. Absolutely. Yeah. I'm, I'm inviting us to. Be more like Jesus, whatever you want to call it. Right, right. And of course, I think. Decolonization is a means to becoming more like Jesus because colonization has shaped us right in the ways of empire, not in the ways of Jesus to resist the ways of Jesus, but decolonization is a means to an end of really becoming more like Jesus, and we become more like Jesus.

At the table when we encounter his real presence, um, through the body and blood of Christ, but also through the larger body of Christ, the church, um, when it's shaped in healthy ways that are connected to the table and the Spirit and to Jesus. And so, uh, yeah, so I I, my, my prayer is that, you know, people are motivated to ask that question of.

You know, how am I, am I being more like Jesus? And um, 'cause you don't see, you know, I talk about this also in the [00:50:00] book when I talk, you know, I take Philippians two. Yeah. And Jesus' posture there. Um. You know, Jesus doesn't take the posture of a teacher when he comes down to earth. Um, he is a teacher. He has answers, right, but he takes the posture of a learner.

And I learned this from Willie James Jennings. Um. On a few of his lectures, uh, Jesus' relationship with Mary, where he says Jesus was a learner with Mary, a woman. Yeah. He, you know, God allowed a woman to disciple him. It was most likely Mary who taught him his prayers as a little child. Right. And. And, uh, and, and so, and Jesus also took the form of a marginalized human being, like an occupied, colonized Jewish, Palestinian man, um, who was poor, you know, uh, and a carpenter, working class family in a refugee family too.

And they fled Egypt, uh, fled to Egypt and his [00:51:00] childhood fleeing violence. And so. I think it's time for us as the Western Church to reckon with the marginalized nature of Christ. Mm-hmm.

Andrew Camp: Um,

Joash Thomas: to be shaped by that. Um, and then to have the eyes to see the holy family in our refugee neighbors, you know? Yeah. To see, to see Jesus in our working class neighbors, to see Jesus among those who are occupied or colonized and have no power.

Andrew Camp: Yeah. No, that's beautiful. I love that. Um, yeah, just eyes to see. Um, you know, and, and yeah. Where, where can I go and meet Jesus, um, in my city of Flagstaff, like on the margins, uh, you know, and I, yeah. Where might that be for me, where that might be for you as a listener? Yeah. You know, where is Jesus calling you?

Uh, that's, it's a profound question.

Joash Thomas: Yes. Yes. And what does it look like to. Be like Jesus on [00:52:00] the margins where you don't come in with answers.

Andrew Camp: Yeah.

Joash Thomas: Uh, but you come in with the posture of a learner. Mm-hmm. Um, to listen with humility and curiosity the way Jesus did with everyone he engaged with.

Andrew Camp: Absolutely.

Uh, and so it's a question I ask and you've hinted at it, but it's a great summary question. Uh, what's the story you want the church to tell?

Joash Thomas: Yeah. Wow. Um, so it's funny you asked this today because we just finalized some stickers, uh, for the book and some graphics that basically say, make the gospel good news for the poor again.

Andrew Camp: Yeah, there you go. Yeah.

Joash Thomas: Nice. And I think, I think that's really what. I want the church to be shaped by. Yeah. Um, even if it's a few people from the church who read this book and their lives are hopefully transformed as a result of the spirit working through my words. I, you know, I want us to remember, and I wanna remind us that the [00:53:00] gospel as defined by Jesus and Luke four 18 is ultimately good news to the poor, you know, and if it's not good news to the poor or the oppressed, or the captive.

Then it's not the good news of Jesus Christ. Mm-hmm. And we need to have the eyes to discern that. Um, you know, so anything that's presented as good news from church leaders, we need to ask ourselves if my black neighbor hears this, if my refugee neighbor, um, if my female neighbors L-G-B-T-Q neighbors hear this, is this actually sounding like good news to them?

Andrew Camp: Hmm.

Joash Thomas: If it's not good news to them, um, then, then it can't be the good news of Jesus.

Andrew Camp: Wow. No, I love that. I really appreciate that. That's a lot to ruminate on and think through. Um, and a fun few fun questions to wrap up that Yeah, I'm, I'm, I'm anxious to hear your responses. So what's one food you refuse to eat?

Joash Thomas: Oh, one food. I refuse to [00:54:00] eat. That is a great question. So I could either go the dietary di direction on this as a preferential direction. Um. You know, I would say overall, I would say anything. Without flavor, uh, without, without spices, without some kind of masala from whatever part of the world.

Andrew Camp: Okay.

That's fair. I, I love that response. Like, I, I've not heard, heard that one, but I No, I agree. Yes. Yes. Anything bland is. Is not worth life is too short to eat bland food. Exactly,

Joash Thomas: and I mean, there's a colonization joke in there for me, which is, look, my ancestors suffered because colonizers came to extract our spices more than anything else.

So I'd be dishonoring my ancestors if I didn't eat food with spice.

Andrew Camp: Yes, I think I saw a meme on face or Instagram from a friend who said, you know if, if you're ever feeling bad about yourself, don't forget that the colonizers came to extract spices and still can't season a chicken.[00:55:00]

Joash Thomas: I, I, you know, my, my rage towards colonialism turned into empathy when I visited the UK for my sabbatical this summer. So, totally get that.

Andrew Camp: Yeah. On the other end of the spectrum, what's one of the best things you've ever eaten?

Joash Thomas: Uh, incredible question. Um

Andrew Camp: hmm.

Joash Thomas: Probably the South Indian style chicken curry I cooked last night.

Andrew Camp: Okay.

Joash Thomas: To be honest, and I mean, you probably feel this as someone who's cooked professionally. Um, once you keep cooking, you probably get to a certain point where you're like, you know, I could probably cook better food than most of the restaurants in my area.

Andrew Camp: Yep.

Joash Thomas: Because I've been doing this a while and, and so I'm very much in the same boat and I, I've learned to enjoy my cooking a lot.

Yeah.

Andrew Camp: That's awesome. And finally, there's a conversation among chefs about last meals, as in, if you knew you only had one more meal left to enjoy, what would it be? So if Joash had one last meal, what might be on his table?

Joash Thomas: [00:56:00] Wow. Wow. Well, not to do a plug to the book or anything, but probably my spicy butter chicken.

Okay. I would ask to cook it for myself again and, and cook it and eat it. And, uh, the recipe for my spice, my spicy butter chicken is actually made available for anyone who pre-orders the book. Okay. You know, and, uh, if you don't get a print copy through Baker Book House, if they run out of those, just DM me and I'll send you a, a digital copy of that if you pre-order the book.

But, uh, but I would say. Um, I, I love butter chicken. Okay. And, uh, so either the butter chicken I cook, or if that's not an option, then uh, any good restaurant butter chicken works too.

Andrew Camp: Awesome. Now. Oh yeah, let's make some butter chicken. Yeah. What do you, do you have a favorite beverage when you eat your butter chicken?

Like, if you know.

Joash Thomas: Yeah. Yeah. I would say, uh, I would say Coca-Cola. Okay. Pretty much works for, for [00:57:00] anything. Um, if I were to go something more Indian, I'd say a mango shake, so I love mango lesses, but I've been appreciating mango shakes a lot more recently and India. Has the best mangoes. I'm very biased, but yep.

I'm convinced India has the best mangoes.

Andrew Camp: Yes. A tropical mango. Yeah. No, there's nothing, you know? Yes. Wholehearted, they agree of Right. Fresh mangoes coming from the true source versus our imported Yes. Mangoes.

Joash Thomas: Yes. And if I've offended. Anyone by talking too much about colonialism here. If I were to, uh, share something good about maybe something that came from colonialism, it was Portuguese mangoes.

The Portuguese brought mangoes from Brazil to India and, uh, contextualize it to India, and, and that's how you have some of the best mangoes in India today called Alfonso mangoes.

Andrew Camp: Oh, I did not, I, I did not know that the mangoes came from Brazil.

Joash Thomas: A lot of them did. Yeah. Okay. The good ones.

Andrew Camp: Well, Joash, I've really appreciated this conversation.

Appreciate your book, your heart. Um, and so if people are wanna learn more [00:58:00] about your work, where can, where can they find you?

Joash Thomas: Yeah, yeah. So the justice of Jesus is available wherever you buy your books. Um, yep. It is, uh, yeah, just, just an honor for me to share. My thoughts and theology and step aside and bring the thoughts and theology of the Global South Church to the Western Church so that we prioritize justice for our marginalized neighbors.

Uh, and then I'm also very active on social media and substack. So my Instagram is where I'm active the most. Uh, it's at Joash p Thomas, and, uh, my Substack is Jesus Justice and Joash. Um, and I'd yeah, love to connect with any of your community there.

Andrew Camp: Awesome. Really appreciate it. Um, and if you've enjoyed this episode, please consider subscribing, leaving a review or sharing it with others.

Thanks for joining us on this episode of the biggest Table, where we explore what it means to be transformed by God's love around the table and through food. Until next time, bye.